FIDE World Championship, 2008

Author’s Note: All emphases within quotes are mine. Books by Anand and other chess greats are the principal sources for this article.

Bonn, Germany, October 2008. Anand will play Vladimir Kramnik for the world chess title. The victor would become the undisputed champion, succeeding Garry Kasparov, who retired in 2005. Anand has to figure out a way to throw the brilliant Kramnik off his solid game and decides to risk it all. He’s searching for the spark of inspiration before his most important challenge since his 1995 World Trade Center showdown with Kasparov.

In a flash of brilliance, Anand abandons his favored 1.e4 opening to play his opponent’s signature 1.d4. This decision was a ‘gut’ call from within that was all wrong in a conventional sense. Though the opening pushed Vishy outside his comfort zone, he believed it would unsettle his opponent even more. It proved successful. Winning the Bonn finals, Anand once again became the world champion.

The western nations have dominated the global chess scene for the past century. Soviet chess players reigned supreme from the 1940s, a time when chess prowess symbolized peak intellectual and strategic dominance. Anand’s journey to the top of chess was unlike any other among his peers. India, the birthplace of chess (Chaturangam), was without a grandmaster until Vishy.

Anand was the one who changed everything.

Anand’s book is available at leading bookstores.

Padma Vibhushan Viswanathan Anand, or ‘Vishy’ as he is known affectionately around the world, is India’s greatest chess player and the original ‘lightning kid’. India’s first grandmaster. First Asian to claim the world’s classic chess title. The best ever rapid chess player. The first to wrest the title from the renowned Soviet chess factory after Bobby Fischer’s Cold War W against Spassky in 1972. The only champion to win the classic chess crown in three different formats: knockout event, 8-player double-round robin, and a final match. His legacy is equally amazing. He has inspired an entire generation of young Indians to take up chess and make a global impact. At the time of writing this article, two Asians, Indian grandmaster Gukesh Dommaraju (also from Tamil Nadu) and Ding Liren from China, compete for the top prize.

Vishy has won a total of 10 world titles in three different categories: classic chess (5 titles), rapid chess (3 titles), and the chess world-cup (2 titles). He’s won several other major tournaments, as well as the de facto (pre-FIDE) world rapid chess championship (Frankfurt/Mainz) many, many times. He’s the inaugural recipient of the Khel Ratna award, India’s top sports honor. Unsurprisingly, he figures in conversations about India’s top three sporting achievers alongside the field hockey wizard, Dhyan Chand, and the cricketing phenom, Sachin Tendulkar.

Vishy, the nice guy next door, the lightning-fast king of 64 squares, trailblazer.

The Lightning Kid

Anand’s birthplace was Mayavaram (now Mayiladuthurai), Tamil Nadu, where he was born on December 11, 1969. Mayiladuthurai’s history is reflected in its many beautiful Kovils (Hindu temples). Anand is the youngest in a family of three children. Thiru. Viswanathan, his father, was employed by the Indian Railways. His mother Smt. Susheela came from a family of lawyers who played chess regularly at home.

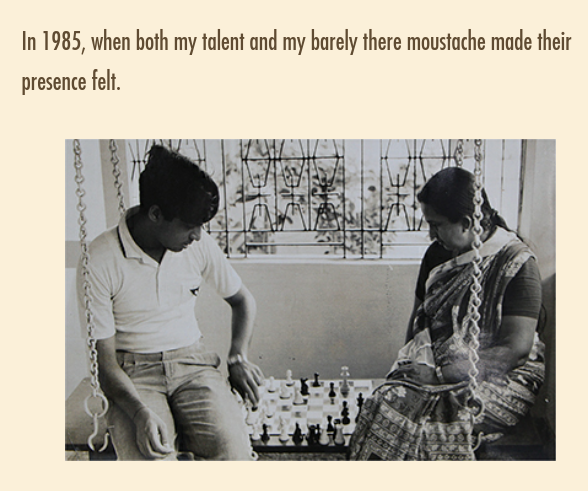

Following a family move to Madras (Chennai), Anand completed his education. At six, Anand’s mother introduced him to chess, greatly impacting his early development as a chess player. He joined the Mikhail Tal chess club in Alwarpet, which was mostly frequented by older people. The club’s co-founder was Manuel Aaron, India’s only International Master at the time. There were no chess grandmasters in India. Anand’s mother signed him up for every tournament the club held, which led to his becoming a dedicated chess player.

Anand moved with his parents to Manila in November 1978 as his father was contracted to do some work with the Philippines railways. His parents took him to the Baguio City venue of the exciting Karpov-Kasparov world chess final, which had concluded weeks before. Years later, he’d win the world junior championship at that same location.

In Manila, Anand and his mother would follow a chess TV show featuring top players’ games. Each episode challenged viewers to solve a chess puzzle and send in their answers by mail. A chess book would be the winner’s prize. Anand won so much the TV show producers gave in, offering him their whole chess library if he’d stop sending them mail. They returned to Madras in 1980.

By age 11, Anand had mastered the rapid ‘blitz’ chess games at the club, consistently defeating most opponents in the popular fast-paced format. Thus began the legend of the ‘lightning kid’. Despite his rising fame, his high school maths teacher, S. Lourduraj, in a Time Magazine report, remembers Anand as being gentle with classmates and respectful to his teachers. 1981 is the year he remembers playing his last chess game with his mother. His mother won.

As a boy, Anand was fascinated by the story of the Ganita genius, Srinivasa Ramanujan. He had read his biography and later, he could also relate to his struggles. Their paths are strikingly similar. Ramanujan’s groundbreaking contributions, achieved without formal mathematical education, kept leading mathematicians occupied for decades. Kumbakonam, under 40 kilometers from Mayiladuthurai, was Ramanujan’s hometown.

In 1983, Anand emerged victorious in the national sub-juniors competition. By then, he had already beaten the nine-time national champion and his Chennai mentor, Manuel Aaron, on two separate occasions. Among the wins was one at the national team championship. Financially strapped, his teen team, the Madras Colts, found a sponsor in legendary playback singer S.P. Balasubramanyam garu. Anand secured his IM norm, then, before he was sixteen and still in tenth grade, he became the national chess champion. He narrowly missed the GM norm in the year 1986. Unaided by any formal system, he became India’s first grandmaster in Coimbatore in 1988. Having conquered domestic competition, he aimed for international success.

"As an Indian, I didn’t know what being a globally successful chess player meant because no one had walked down that road." - Viswanathan Anand.

Anand gained a reputation as a speedy player. Canadian-Russian player Evgeny Bareev remarked that Anand had a unique ability to see more on the board than most other players could in the first minute of play. In the international circuit, his challenge was to learn and continually improve by analyzing the games between top players.

Chess, originally chaturangam, was invented in India and was used to teach strategy to young princes.

A Siva Temple associated with a game of chess. https://t.co/TVAFMJ6mmG pic.twitter.com/P7ubgClwTl

— Chithra Madhavan (@ChithraMadhavan) December 2, 2024

In India, by the 1970s, chess was unfortunately reduced to just another pastime board game. Chess even symbolized political and cultural decay. The 1977 movie ‘Shatranj ke Khiladi’ by Satyajit Ray portrays two chess-obsessed noblemen engrossed in the game and oblivious to the surrounding events. It was a world apart from modern New India. There was no system in place to train players. For example, Dibyendu Barua was another promising junior player of the 1980s. He had the talent (India’s second grandmaster) but could not make the leap to the international stage.

Let’s examine this example. Anand received a computer in Europe in 1987 to help him prepare for chess. His application to bring it home took 8 months for New Delhi to process and approve. Then, the Chennai customs added another layer of difficulty, slapping a 250% duty on the item. Outside pressure and media attention helped him finally bring it home.

His B.Com graduation from Chennai coincided with a world ranking of fifth place for him. To compete in Europe’s top tournaments and cut down on travel costs from India, he moved to Madrid. He went pro circa 1993-94, and his ranking climbed throughout the 90s. Anand narrates an interesting incident that occurred just after he turned pro: “On a train journey to Kerala, a well-meaning gentleman sitting by me asked me what I did for a living. When I responded that I played chess, he smiled and offered that it wasn’t a secure career. ‘Not unless you are Viswanathan Anand,’ he concluded. I listened and nodded sagely, and didn’t confess to being the person he was referring to. It is a compliment I still hold dear.”

Anand versus the Soviet Machine

It is important to understand the nature of the multi-dimensional challenges that Anand faced in the first half of his career.

Anand played in a 1991-92 Italian ‘Super Grandmaster’ tournament where the rest (nine of them) were all top Soviet players. Anand triumphed in the tournament, beating out chess legends Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov. Symbolically, halfway through the tournament, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. By 1995, he had earned a match against Garry Kasparov for the world title.

"I always felt that I had the advantage in calculation over anyone except the Indian star Viswanathan Anand, who was justly famous for his speedy tactical play." - Garry Kasparov.

The Anand-Kasparov contest attracted worldwide attention. No non-Soviet origin player had reached the top after Bobby Fischer in 1972. Here was a contender who was completely outside the Soviet/European system. He learned his chess in a largely unstructured environment. He used his speed, sharp board sense, and ability to thrive in chaos to his advantage.

In contrast to the era’s stereotypical sullen and egotistical genius grandmasters, Anand was refreshingly different. Regular guy Anand’s interests included Monty Python and Pet Shop Boys’ music. “Anand wasn’t some arrogant brat; sure, he was self-confident, but he had a healthy sense of humour and was quite prepared to laugh at his own mistakes.”

Anand’s chess game diverged from the robust and orderly school of Soviet chess that was built on decades of top-tier experience, a human bank of domain expertise, and the mastering of theory. Eastern Europe and Russia have produced some of the world’s best pure mathematicians. Anand faced a chess dynasty renowned for their winning strategies and ability to avoid losses in protracted championship battles. It was Anand versus the machine.

The challenges Anand faced before the internet are fully revealed in his autobiographical book. Initially, the Soviets wrote him off as a mere ‘coffee house player’. The ‘upstart’ with an unpronounceable surname (which the west mistook as his ‘first’ name, which is Anand), from an unknown part of India. In the pre-internet days, Anand used faxes to receive chess information and updates on major games from his friends in Europe. He recalls “The Soviet Union, so far, was in a yawning lead over the rest of the world when it came to chess–in experience and expertise–and access to information from there was considered the Holy Grail… The closer to the inner circle you were (in this case, Moscow), the greater the quantum of information and the finest expertise that you had at your disposal..”

In the US-USSR Cold War, a chess master turned spy embodied the quintessential movie villain from the other side of the Iron Curtain.

On the surface, chess seems calm, yet it can develop into a fierce mental struggle with unseen consequences. You don’t just make ‘mistakes’ on the board, you commit ‘blunders’. The original ‘chaturanga’ in Sanskrit denotes the four limbs of a military formation in ancient India.

Each of the prior battles for the world crown, including Fischer-Spassky, Karpov-Korchnoi, and Kasparov-Karpov, were all high-voltage drama fueled by politics, intrigue, and gamesmanship. Bobby Fischer openly relished the moment he broke his opponent’s ego. Soviet-era players were brilliant, tough, and battle-hardened survivors. For example, Garry Kasparov said this about Viktor Korchnoi: “he enjoyed grabbing a pawn even if it meant weathering a brutal attack. A man who had survived the Siege of Leningrad as a boy was not going to be intimidated at the chessboard.”

The original World Trade Center’s 107th floor observation deck hosted the Anand-Kasparov match. The first eight games ended in a draw. When asked about this, Anand famously told journalists, “It’s not rock and roll“. Winning the ninth game, he took the lead and thrilled his Indian fans. The remaining games went downhill. Vishy lacked championship preparation experience, and his game became predictable, leaving him exposed in the backend of the championship.

Utilizing computer-based preparation, a first for Kasparov’s team, would provide an advantage if Anand repeated a pattern. Kasparov, in his own words, was relieved when Anand did just that, and end was swift. Many consider Kasparov the greatest chess player ever, and Anand almost dethroned him but fell short. In his own words: “Frankly, I was not ready for a match of that magnitude. At the time, computers were nowhere close to performing the way they do now and the match taught me how much I had left to learn. Looking back, I’d say the volume of preparation I did through the match is perhaps what I do now in a day’s time.”

AI-powered data analysis of every world championship game (1886-2023) reveals the 1995 edition as the most accurate ever. It had the fewest ever missed points by either player.

Anand uniquely remained a top chess contender from the 1990s (pre-internet) through the 2010s (computerized chess). The impact of experience is diminished now, Anand notes, because of powerful software, hardware, and large databases facilitating comprehensive opponent-specific preparation. His lack of experience and Soviet chess school background put him at a disadvantage in the 1990s, a time when these factors were crucial. They could turn the contest into one around the openings and put Anand at a disadvantage through ‘opening pressure’.

IBM Deep Blue’s 1997 chess victory over Kasparov stunned the world, marking the dawn of the machine age. Anand realized that powerful computers could negate the Soviet machine’s advantage. He mastered computer-driven preparation through hard work and a significant learning curve. He reaped the rewards, whereas older players such as Karpov had more difficulty adapting. Anand outplayed Karpov 5-1 in a one-on-one human + computer contest held in 1999. Technology has steadily improved the accuracy of the championship finals over time, reducing errors. Today’s computing power has made chess much more accessible, and we’re seeing top players from all over the world.

The Tiger of Madras

“Thambi kaisa? tiger jaisa. Tiger kaisa? Vice versa!”

Madras is famous for two tigers. One is the soldier of the Madras regiment, the thambis of India’s storied and oldest infantry unit. The other is Anand, although he was not a big fan of this sobriquet: “The thing with the tiger was an invention by some journalist who probably could not think of any other Indian animal. Normally I avoid conflict, and I am indeed not a killer like Kasparov.” As a fan, I’d say the tiger is India’s pride; majestic, spirited, fast, and a master of the chaotic jungle.

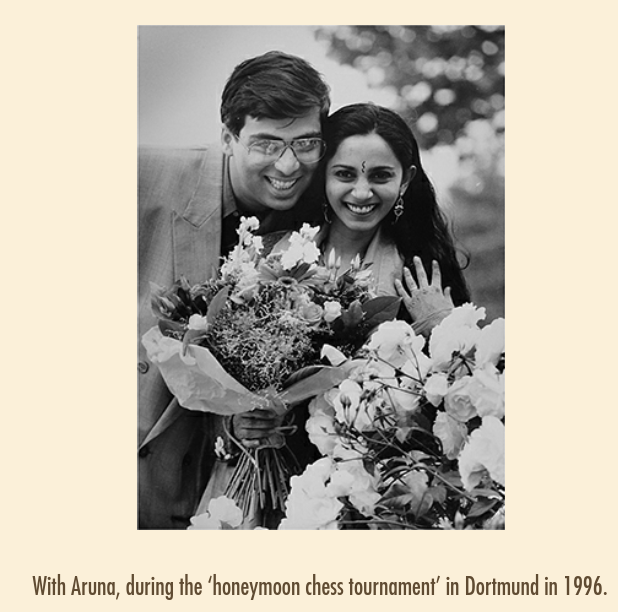

Anand married Aruna in 1996 who took over the ‘baton of handling everything in his life, apart from chess’. With championship experience under his belt and the support of Aruna, Anand’s chess grew stronger.

The chess world was being torn apart by politics and bias. Players like Anand who did not belong to any faction endured a tough time. A knockout tournament supplanted the candidates tournament in 1997-98 to determine the World Championship challenger. Only three days following that tournament, the victor would contend with Karpov for the global championship. Both Kasparov and Kramnik pulled out since this gave an undeserved privilege to Karpov. Anand won the tournament, needing to arrive at the championship venue within 3 days. He recalls “We somehow managed to get ourselves on a plane and landed in Lausanne, only to learn that FIDE had booked all its officials into hotel rooms but had made no provision whatsoever to accommodate the winner of the 21-day-long knockout tournament that was a qualifier for the final. Once again, we were left to wage a logistics battle on our own“.

Despite the tough conditions, Anand’s brilliant final performance, including a comeback to force a tie, was tragically ended by a rapid chess tie-breaker loss. In his words, it was like being asked to “run a 100-metre sprint after completing a cross-country marathon.” The ex-Soviet player made matters worse by questioning Anand’s championship-winning ability, despite the huge advantage he had created for himself. By 2000, his arch rival (and friend) Kramnik defeated Kasparov for the world title. While Anand came close to overcoming two of the Soviet system’s all-time best, he remained without an ‘undisputed’ world title.

Kramnik once said that all pros know this about chess: you can play well, even beat Anand, but avoiding time trouble is impossible.

Having won the Y2K FIDE knockout chess championship, Anand challenged Shirov, another former Soviet Union player with a past victory over Kramnik. The final was held in Tehran and Shirov was no match for Anand in the finals. Anand finally became a World Champion. Anand was at his best in the 2000s. His decisive win against Kramnik in Bonn during 2007, following Kasparov’s 2005 retirement, stands out.

The final match in 2010 against Veselin Topalov, held in Bulgaria (a nation previously part of the Soviet bloc), stands out as another remarkable event. Amid a Europe-wide volcanic storm that grounded flights, Anand’s team had to journey across 4 countries and 2000 kilometers. There was not much help from the tournament organizers. To reach the venue, Anand and his team had a race against time, traveling by road and even taking a ferry. A Bulgarian police officer pulled them over for speeding, and exclaimed, ‘Ah, you’re Vishy Anand? You’re the guy we are searching for; please don’t drive as fast as you play!.’ Anand and his team had spent more than 40 hours on the road to reach their location three days before the first match. To worsen the situation, it was revealed that Topalov used a 112-core computer cluster with state-of-the-art chess software, compared to Vishy’s basic 8-core machines. Anand could only imagine the kind of edge such computing power would offer. The same system was not made available to Anand.

Anand came up with a strategy to negate his opponent’s strength: play non-computer chess and land the first punch. He went back to his strengths and relied on spontaneity and surprise by mixing things up unpredictably. This would reduce Topalov’s computational advantage; no predictable patterns would exist for planning or exploiting in later games.

The game area was also a site of psychological warfare. Anand later learned that his team had to employ an undercover agent to screen their hotel rooms for listening devices or cameras planted by his opposition. In a remarkable turn of events, past rivals Kasparov and Kramnik offered to help Vishy through video calls and notes. Anand recalls this contest as a battle between a ‘human cluster’ versus ‘computing cluster’. The evenly balanced contest was heading towards a rapid-chess tie-break. Topalov, sensing Anand’s advantage in a rapid chess shootout, gambled, overextended, and lost. Anand successfully retained his title.

Return of the King

Anand successfully defended his title once again in Moscow in 2012 against Boris Gelfand of Russia. During his meeting with Russian Premier Vladimir Putin, he revealed that he learned chess early on at Chennai’s Mikhail Tal club. Putin remarked, ‘Oh, so you’re a problem we brought upon ourselves!’

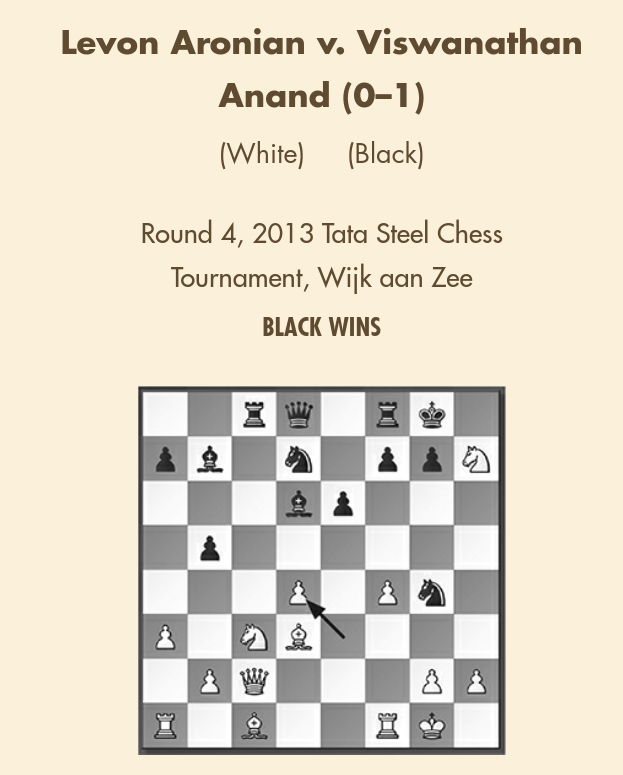

Anand had reached his peak. Over the next two cycles in 2013-14, Anand lost his title to Norway’s Magnus Carlsen (considered by many to be the greatest ever). Carlsen forced Anand to play ‘dry and bloodless’ positions and long games that Anand found difficult to manage. Interestingly, Anand picks his 2013 Tata-Steel Group- A game against Levon Aronian as the best game he’s ever played. “Every player goes on to create that one thing of absolute, peerless beauty. This one was mine.”

Anand had one last, impressive move remaining, however. Nearing age 50, he almost skipped the 2017 Rapid Chess Championship in Riyadh, but his wife Aruna felt he had nothing to lose: “Apidi enna thaan aagum?” (what’s the worst that could happen?). Twenty-two years after his first duel with Kasparov, the Tiger of Madras turned back the clock and played fearless chess to win the rapid chess crown. He defeated Magnus Carlsen enroute to an undefeated tournament performance.

A recent study of over one billion moves of top-players used AI to analyze the data from all world championship games between 1886-2023. It reveals Anand’s ‘Game Intelligence’ is second only to Carlsen’s. Anand also has the best accuracy in these contests, as measured by the lowest Game Point Loss (GPL) among all players. Combine this accuracy with his naturally fast game that was entirely self-taught, and we get an idea of what a phenomenal player he is.

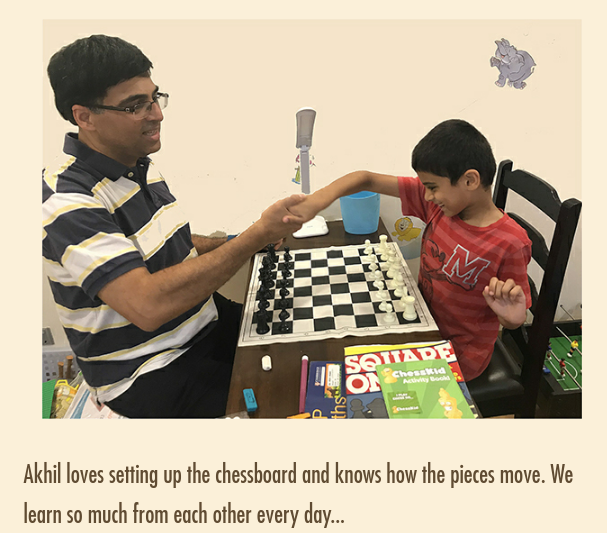

Peak chess performance, much like in other sports, decreases with age. Even at 50 (in 2019), Anand’s high ranking was noteworthy. He remains involved with the game today. He spends more time with his son Akhil who was born in 2011. “Mind Master,” by Anand, offers incredible perspectives on his thought process and decision-making, which can be beneficial to everyone. He uses public speaking to share his learning and experiences, and works with ‘Olympic Gold Quest,’ an Indian non-profit organization for aspiring Olympians.

Here’s an incomplete list of awards won by Viswanathan Anand. Here’s a list of all major tournaments and championship performances. In 2007, he received India’s second highest civilian honor, the Padma Vibhushan.

A generation of young Indian chess players found inspiration in Anand’s achievements. But, according to Anand himself, he’s there not to preach boring nostalgic sermons but to share his learning and experiences. Winning double gold at the 2024 Chess Olympiad signifies India’s remarkable progress in chess, a stark contrast to the era when Viswanathan Anand was the lone player. More and more Indian players are achieving ELO ratings above 2700, and even 2800. To this day, Anand maintains his deep love for chess, stating, “the root of the matter remains that I like playing chess. It’s the warm, familiar feeling I circle back to every time.”

Truly a Bharat Ratna.

References

Viswanathan Anand and Susan Ninan. Mind Master: Winning Lessons from a Champion’s Life. Hachette India. 2022.

Garry Kasparov. Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. John Murray Press. 2017.

Vishy Anand and John Nunn. Vishy Anand: World Chess Champion (Chess World Champions). Gambit Publications. 2012.

Mehmet S. Ismail. Human and Machine Intelligence in n-Person Games with Partial Knowledge: Theory and Computation. Arxiv.org. Revised, 2024.

Steve Wulf. A New High for Chess. Time Magazine. 1995.