Table of Contents

Summary

Tamizhs have a long and distinguished history of trade and commerce. The history, culture, and sci/tech pages provide an overview of the business, manufacturing, and commercial activities of the Tamizhs during historical times. The history page provides an overview of the ancient Tamizh economy, how it functioned, and how well it was organized. Today, Tamil Nadu (TN) is one of the most economically developed states in the Indian union, and its diverse business sectors are lucky to count a large number of entrepreneurs among their ranks. TN is considered to be the most industrialized state, and the second largest in terms of GDP in India (among the top 50 economies of the world by some accounts). In particular, one will discover that the contributions of TN’s ‘unorganized’ sector played a crucial role in this success. Contemporary Tamil Nadu is a major manufacturing and IT hub, while also continuing to progress in its traditionally strong areas such as agriculture, textiles, arts & craft, fisheries, and trade.

“Tamil Nadu’s Contribution to India’s Industrial Output” by KARTY JazZ – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Commons.

Tamizhs: Global Business and Management Leaders

Tamil Nadu has produced many domestic and multinational companies, and several notable industrialists, management experts, and business leaders including Shiv Nadar (HCL), C. K. Prahalad (strategy wizard), Indra Nooyi (current CEO, PepsiCo), and Sundar Pichai (current CEO, Google, Inc.) Tamizh business leaders have followed a dharmic culture of philanthropy, social, and educational services since ancient times (see the history page), and the tradition has continued to this day. The contributions of Alagappa Chettiar, Raja Annamalai Chettiar, Arcot Narayanaswamy Mudaliar, Mahalingam Gounder, and several others, are laudable.

“Shiv Nadar, Founder, HCL and Chairman, HCL Technologies. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons.

In this page, we provide some historical details about the Indian economy in general, and call out points of interest to Tamizhs before moving to a contemporary study. Rather than follow a standard English textbook approach of analyzing the Indian economy using a western universal lens and focus on stock market vs centralized government planning, we opt for a ground-up approach using a native Tamizh and Indian perspective, just like we have attempted to do in the other pages. To gain insight into the Indian approach to business and commerce in Tamil Nadu and India, we rely on three data-driven sources:

- a) The Indian business models studied by Professor P. Kanagasabapathi [1]

- b) To understand the economic landscape of India and Tamil Nadu, we note the findings of Professor R. Vaidyanathan [2] at IIM Bangalore

- c) we refer to the lecture series at IIT-Bombay by writer and commentator, S. Gurumurthy [3] to understand how the Indian approach to economics is different from the Western alternatives

(all image links from amazon.com)

Some of the research findings and next steps recommended within these references are being acted upon by the incumbent Government of India.

Brief History of Tamizh Business, Trade and Commerce

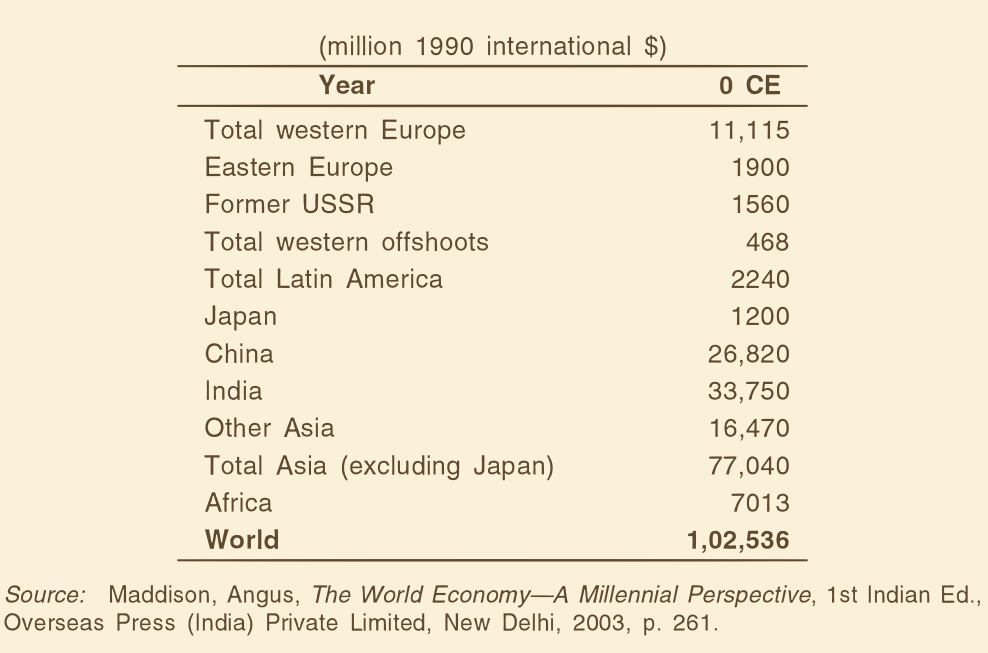

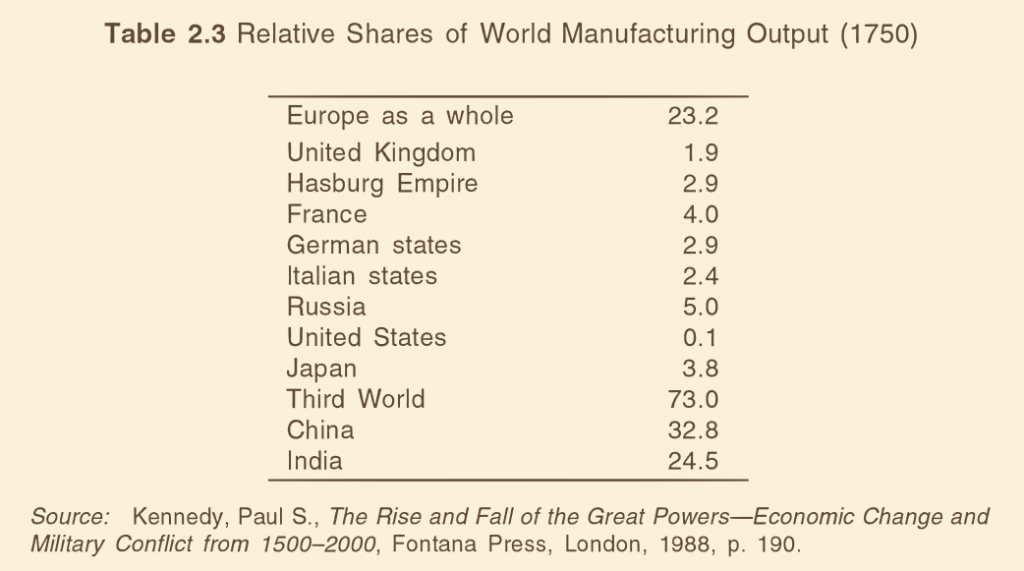

We start off with two data points related to the world economy from [1]: The national GDPs in 0 CE (common era), and the national market shares of global manufacturing output in 1750 CE.

The GDP and manufacturing/economic data sampled at regular intervals between 0 CE and 1750 CE supports the statement that India was a leading (either #1 or #2 along with China) economy of the world. The stable society as well as the scientific and technological developments needed to maintain this lead was also available (some examples are given in the history, and the science and tech pages), and since the time of Kautilya’s Arthashastra, the Indians have had a deep understanding of the importance of economics, and how to achieve the right balance based on the Purusharthas. The temples of Tamizh Nadu were also decentralized financial and economic institutions, as discussed in the history page.

Seven years before the battle of Plassey in 1757, India’s manufacturing output was more than that of Europe and USA put together. The ruin of India’s economy, its educational, and cultural institutions, destruction of its manufacturing units, and piracy of its intellectual property was triggered by the British occupation of India. Great thinkers, from Dadhabai Naoroji to Dharampal have written about this. Famines that were practically unknown before, was commonplace during the British Raj, culminating in the horrific Bengal holocaust of 1943, where an estimated 4-6 Million Indians perished. India become an impoverished nation by the time the British pulled out shortly after WW2.

After its political independence in 1947, India failed to achieve economic independence. It did not adopt an India-centered approach that their ‘Father of the Nation’ Gandhiji had strongly advocated in his 1909 book ‘The Hind Swaraj’ [4]. Rather, it was enthralled by the propaganda of the ‘progressive’ socialist/communist model of the Soviet Union. This western model was chosen in order to implement centralized planning, even as a large part of the Indian economy continued to operate, with no government support, based on traditional methods. Soon, this centralized planning approach turned into a nightmare. It created a bloated and corrupt bureaucracy that served little purpose except to perpetuate the miseries experienced under the British Raj. Millions continued to live in abject poverty, with no basic amenities. Economic growth was stunted, even as the more educated students exited the country to greener pastures in the developed west, leading to a ‘brain drain’. This socialist experiment which was initiated without a clear understanding of the fundamental realities of the Indian society and foisted on an unsuspecting public, was eventually recognized as a utter failure even as its author, the Soviet Union, collapsed. India, a leading economy for more than 1700 years, stood on the brink of collapse. Finally, more sensible alternatives were adopted by Prime Minister Narasimha Rao in order to solve India’s economic problems.

The progress since the 1990s has been slow, and entrenched left-wing interests have continued attempts to revive their failed approach, while some right-wing proponents rooted in consumerism advocated a shift to the other western pole. This is not surprising given that the views of two leading western thinkers, Karl Marx and Max Weber, who neither set foot in India, nor had a first hand idea of what Indian civilization was about, dominated the minds of the English-educated Indian elite for several decades [3]. Today, India is on the rise again as it strives for the economic independence that eluded it for the last two centuries. John Galbraith, in 2001 noted: “I wanted to emphasise the point, which would be widely accepted, that the success of India did not depend on the government. It depended on the energy, ingenuity and other qualifications of the Indian people. And the Indian quality to put ideas into practice. I was urging an obvious point that the progress of India did not depend on the government, as important as that might be, but was enormously dependent on the initiative, individual and group—of the Indian people.“. Neither free-market theorists nor the socialist government can claim to have played the starring role in India’s resurgence in the 21st century. As Prof P. Kanagasabapathi notes: ” the people of India have been shaped by a unique set of social and behavioural systems driven by the age-old culture that mandates family life, hard work, savings orientation, entrepreneurship and a self-dependent mindset. It is this background that drives India to higher levels; it is not the bookish theories or policy prescriptions based on outside experiments. Even the government and state agencies seem to play only a limited role. The forces behind India’s development seem to be more internal than external.”

A necessary (if not sufficient) condition to achieving sustained improvement is that Tamizh and Indian leaders have to first comprehend and internalize this unique Indian approach to economics, business, and management. Let us dive deeper into this topic.

Business and Commerce in Tamil Nadu Today

Per [3], the two salient features of India’s economy are: it is feminine in nature, with the family as its fundamental economic unit. How?

Family: Fundamental Economic Unit of India

The traditional Indian economy is neither truly capitalist nor communist, but dharmic. Dharmic, in the sense that its players seek a resilient and sustainable solution that can (only) be achieved without external, centralized control or unbridled profit maximization, in order to benefit every stakeholder, including the environment. Simply put, the success of this Tamizh and Indian approach to business over the centuries, and to this day, lies in following the Grihastashrama dharma and pursuing the Purusharthas (see the dharma page). The family is India’s primary economic unit – about 66% of India’s income comes from the family-based sector [1]. Since times immemorial, the wife or the mother is the Grihalakshmi, and the ‘CFO’ of the Indian family. She holds the keys to the family ‘treasury’. An important event in the ancient Tamizh epic Silapathikaram occurs when Kannagi lends her precious anklets to her husband Kovalan, in order to generate the initial capital required to restart his collapsed business and recover their lost wealth. Key decisions, especially economic ones, are rarely made individually, but in consultation with elders in the family. In Hindu tradition, businesses are almost always started, and existing ones managed, keeping in mind the needs of a family, rather than those of an individual. The entire family contributes investments, and the role of its CFO is crucial. The fundamental truth claims in dharmic thought systems (Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain) of Karma and rebirth silently play a positive, as well as self-regulatory role during this decision making process. Clearly, the motivations here are different from those seen in individualistic and/or materialist-theory driven societies seen in the west. Consequently, any analysis, however sophisticated its math may be, which ignores these fundamental realities of the Indian society is unlikely to produce a reasonable working model. Such top-down models become useful if and only if a significant proportion of the population are forced to alter their normal behavior in order to satisfy the (unrealistic) modeling assumptions!

Banks and Savings versus Stock Market and Spending

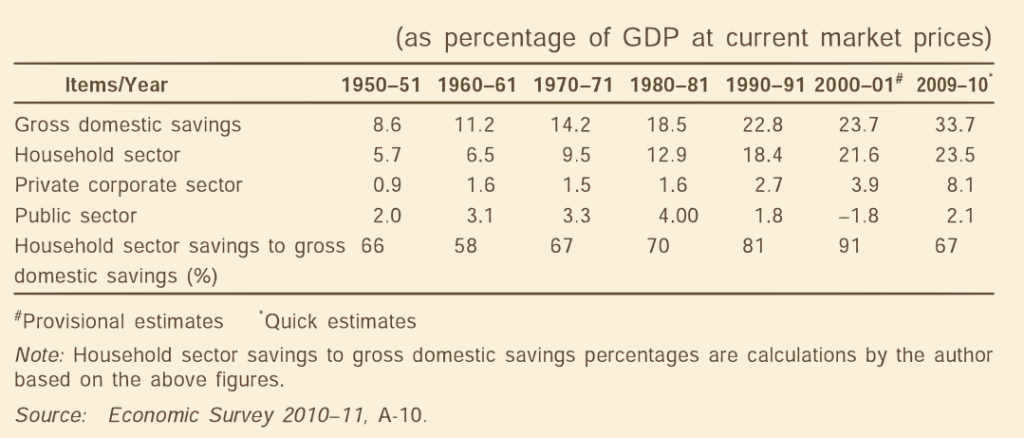

Saving, rather than spending, is considered a virtue in the Indian society, and India has one of the highest savings rates in the world. Indian family members save as much as feasible by employing a variety of methods [1, 2].

This popular song written by Kannadasan for K. Balanchander’s movie ‘Bhama Vijayam’ highlights the benefits of savings, a balanced Indian lifestyle over profligate consumerism, and the pitfalls of spending beyond our means. Thus, the Indian family is wise in that it seeks long-term solutions: it is willing to forego spending for immediate gratification in order to be in a better position to manage an economic downturn tomorrow. Economic data clearly shows that the growth in savings rate mirrors the improvement in the Indian economy over the last few decades, as shown in this table below taken from [1].

The savings can be in the form of gold, savings bonds, chit funds, bank deposits, life insurance funds, etc, with a preference for secured, rather than risky investments. In keeping with this theme of ‘self-sufficiency’, it is not surprising that Indians invariably prefer to be self-employed, whether they are in India or overseas.

Self Employment

The Vidura Neeti from thousands of years ago promotes the virtue of being self employed. A 2005 survey [1] shows that approximately 60% of rural workers are self-employed. Self-employment in India can also be viewed as a duty based economic activity as against a rights based contractual employer/employee model that is common in the west. India has among the highest per-capita entrepreneurs in the world, who contribute to a staggering 30% of India’s GDP and 45% of India’s income tax [1]. Bulk of this sector is operated by SC/ST/OBC sections of the Indian society. Clearly, the self-employed segment is a very important driver of India’s economy, and yet, has received little attention until very recently, with the incumbent government’s launch of Mudra initiative, etc.

Read here about the amazing story of Doraiswamy Naidu, an entrepreneur who was born in an agricultural family. Some regard him as the pioneer of the modern automatic shaving razor.

Here is a 2015 talk by Rangaraj Pandey, Chief News Editor, Thanthi TV given to students on the benefits of entrepreneurship (in Tamizh).

Trust, Social Capital, Jati, and Beyond

A thriving family system, and a stable government are necessary, but not quite sufficient in the long run. For sustainable progress and growth, India requires trust networks that bridge the large void between the family and the government. These systems of trust are required to make economic models more scalable while keeping transaction costs down [7]. They facilitate the transition from a small, family-run business to a professionally managed profitable enterprise that is self-sufficient and does not rely on Government handouts. Such systems also contribute to the social capital of a nation. The key idea emerging from the the works reviewed in this study is that ‘a quest for economic prosperity, business and commercial success unites people within and across Jatis as a centripetal force, whereas ‘politics and power play’ is divisive and centrifugal in nature. In India, the former is an example of social capital [7] being put to beneficial use toward achieving the purusharthas. It enhances trust, preserves mutual respect, and hence promotes stability, whereas the latter is a squandering of hard-earned social capital, which can produce short-term benefits, but eventually results in increased adharma, and instability.

What is Social Capital?

Francis Fukuyama in [7] lays out detailed ideas on social capital. We refer to some passages from this essay and [6] that refer to fairly universal observations that also take into account the specific cultural context, which can be used to better understand the economy and politics of Tamil Nadu and India.

Fukuyama defines social capital as “an instantiated informal norm that promotes cooperation between two or more individuals. The norms that constitute social capital can range from a norm of reciprocity between two friends, all the way up to complex and elaborately articulated doctrines like Christianity or Confucianism. They must be instantiated in an actual human relationship: the norm of reciprocity exists in potentia in my dealings with all people, but is actualized only in my dealings with my friends. …”

On the need to specify a clear set of norms:

Not just any set of instantiated norms constitutes social capital; they must lead to cooperation in groups and therefore are related to traditional virtues like honesty, the keeping of commitments, reliable performance of duties, reciprocity, and the like. A norm … which enjoins individuals to trust members of their immediate nuclear family but to take advantage of everyone else, is clearly not the basis of social capital outside the family..

On the positive as well as negative externalities that social capital can produce:

…. In Partha Dasgupta’s phrase, social capital is a private good that is nonetheless pervaded by externalities, both positive and negative.… Negative externalities abound, as well. Many groups achieve internal cohesion at the expense of outsiders, who can be treated with suspicion, hostility, or outright hatred. Both the Ku Klux Klan and the Mafia achieve cooperative ends on the basis of shared norms, and therefore have social capital, but they also produce abundant negative externalities for the larger society in which they are embedded.”

This is an important point. Why does social capital have the potential to produce negative effects?

“…. This is because group solidarity in human communities is often purchased at the price of hostility towards out-group members. There appears to be a natural human proclivity for dividing the world into friends and enemies that is the basis of all politics It is thus very important when measuring social capital to consider its true utility net of its externalities.”

Simply put, net value of social capital in a system = incremental benefit to those inside the group minus the incremental loss to those inside the system but outside the group.

Social capital plus dharma

Like any other capital, social capital can be used or misused. Let us use the concept of ‘family’ to evaluate the above equation to see how the net value of social capital in a system can be maximized in multiple ways.

- One way to generate a sufficiently huge benefit to those inside the group is at the expense of a large loss borne by those outside the group, such that the net value is also large. Such an approach discriminates between those ‘inside’ the immediate family or jati, and those outside. This is an imbalanced situation and is likely to be unsustainable.

- A better alternative is the ‘extended family’ approach that seeks a Shubh Laabh to achieve a more balanced profitability for those inside the group without harming the interests of those outside the group. When social capital is further bound by the principles of dharma (in particular, Ahimsa encapsulates the idea of minimizing the harm to the cosmos by action or inaction), it becomes a truly sustainable and positive form of capital, and it is this form of social capital that India can practically strive for and build upon. A well known success story of the duty-based Hindu business approach that accumulates and positively uses social capital is the Mumbai Dabbawala.

- Under dharma, those outside the group includes not only humans, but also animals, plants, and the environment, and thus represents a most integral approach. Indeed, the noblest approach to accumulating social capital that has ever been conceived of, is the one based on the Hindu ideal of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’, where the entire cosmos is family, and no one is left out.

To summarize, when social capital is accumulated and used in a dharmic manner, it minimizes the degree of negative externality, and therefore the prosperity that results from such an approach is also likely to be more stable and lasting. In Indian business and commerce, Jati as social capital was historically managed in this positive manner (see references). We examine a case study in Tamil Nadu later in this page. On the other hand, when Jati is used for vote-bank politics in order to achieve economic gain (a trend in the last few decades), the benefits accrue to those within the group at the expense of those outside. This approach is adharmic and unstable due to the inevitable backlash from those outside, and eventually harms the entire system.

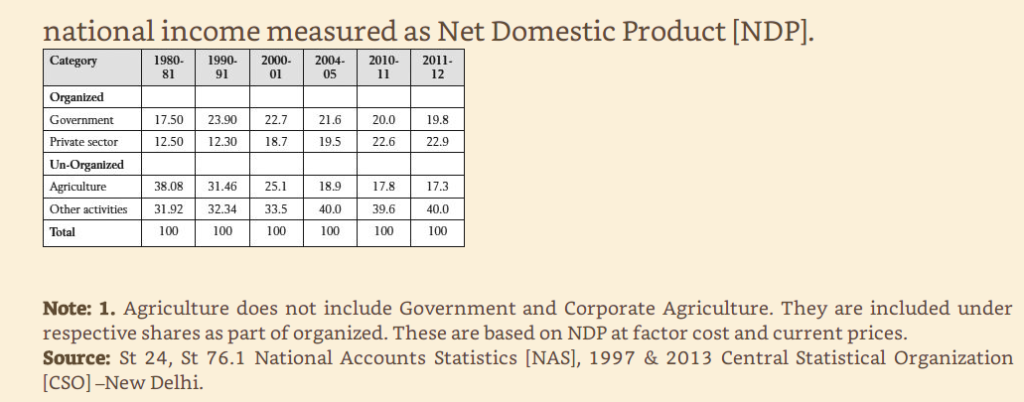

India, Uninc

India Uninc [2] can be defined as “the non-corporate sector as those non-corporate entities which belong to non-agricultural and non-government [departments and non-departmental enterprises] activities. It excludes company forms of organizations in the private sector and also in the public sector..”. The Uninc contribution to the Indian economy is quite critical and contributes roughly 45% of the national income, dwarfing the corporate sector, whose contribution is around 15%. This picture from [2] conveys the importance of the non-corporate sector to the Indian economy.

Industrial clusters represent an important segment of the economic activity within India’s non-corporate sector. After a brief discussion of the key features of industrials clusters, we conclude this page with a case study.

Top 10 Features of Industrial Clusters

Industrial clusters are a crucial part of the Tamizh and Indian economy and are mostly related to the manufacturing sector. Ten salient features of such clusters given in [1] are listed below with additional comments:

- They are managed, and operated by ‘ordinary’ Tamizhs: This is an extraordinary fact, given that many of the successful people in these businesses come from a modest and humble background, with neither the English nor the college degree that most urban Indians so desperately seek. These are self-made, entrepreneurial Tamizhs. Many of them are farmers who have turned exporter, and they employ foreigners to better manage their international operations. They also hire MBAs to professionally manage some day-to-day aspects of their enterprises.

- High on skill and practical knowledge, low dependency on the book-learning approach available in India’s colonial education setup.

- Relationship-driven business and trust-based transactions: It is worth pointing out that their relationships are not static and thus not restricted to their immediate family, or own Jati. Over time, these relationships transcend identities and shed the baggage of negative externalities they tend to come with. Doing so allows them to be construct scalable enterprises that can be professionally managed by the most capable, trusted, and qualified people chosen from a large pool of candidates. Here, we see a contemporary example of Jati as social capital with minimal negative externalities.

- Highly entrepreneurial.

- Largely self-sufficient, and not state-dependent: From (3), (4) and (5), it is interesting to see that these clusters are neither truly western-capitalist, nor western-communist in their approach, but rather, represent a uniquely decentralized and scalable Indian business model. This is exactly the kind of approach that we observed in the history of Tamil Nadu. If anything, government corruption and the instability inducing casteist politics (e.g. in the form of Jati based ‘vote banks’ that produce severe negative externalities) are the biggest impediments to their success.

- Generation of funds and savings from local sources enhances financial robustness and sustainability by reducing risky external dependencies.

- High levels of cooperation and competition.

- Striving for Innovation and Improvement. Customers stand to benefit the most from (7) and (8).

- Global Business Centers.

- Drivers of economic development. The economy in and around these clusters benefit, and grow too.

Finally, we review a concrete example of an industrial cluster in Tamil Nadu and see how all the Indian business concepts discussed so far in this page come together to create the Tirupur success story.

Case Study: Tirupur Industrial Cluster

Tirupur is world-famous for its knitwear and its FY 2010-11 exports was more than USD 2 Billion. 92% of its entrepreneurs come from a poor community that had a farming background, and have gone on to become exporters, making a mockery of western Marxist theory [1]. They form Tirupur’s social capital. Roughly 70% of them have secondary education or less. Their success rests on the fact that their businesses are organized on the basis of relationships that tend to unify Indians and transcend narrow sectarian boundaries, as noted in [1], “A close-knit relationship exists among people of all communities, irrespective of their caste, region and religion. There are businessmen from all parts of the country in the Tirupur cluster today“. The nature of their trust network is such that they do not depend on the state to satisfy their needs, and form private organizations to develop their cities and enable public infrastructure development, and complete these projects much faster than governments would. Tirupur also offers example of individual initiative to improve the standard of living of the people working there. Some have constructed houses with their own money for employees, thereby enabling them to become home owners, with mortgage plans offered under fairly relaxed terms and conditions.

Women play a crucial rule in terms of savings and also providing capital. The word ‘Lakshmi’ is not only symbolic, but also practical. Capital required for these businesses and their expansion is generated from diverse sources, including family, farm, and prior earnings (often up to 85% is saved). For example, the successful Viking brand of hosiery products in India was financed by the maternal grandmother by pledging her jewels and lands.

To summarize, [1] notes: “The World Bank has acknowledged that the community-based relationships help business to become competitive in the international markets. The World Development Report 2001 reveals as to how the majority community of Tirupur was able to succeed in the knitted garment industry due to the transfer of capital through community networks….. These networks were viewed as more reliable in transmitting information and enforcing contracts than the banking and legal systems that offered weak protection of creditor rights. The intense competition in the garment industry ensured that good money would not follow bad and that firms would pay attention to the needs of customers.”

The Tirupur industrial cluster accounts for more than 44% of the total knitwear exported by India today [Ministry of Commerce web site: 2014-15 FY]

References

1.’Indian Models of Economy, Business and Management‘, by Prof. P. Kanagasabapathi. 3rd Edition, PHI Learning (2012).

2.’India, Uninc‘, by Prof. R. Vaidyanathan, Westland (2014).

3. IIT-Bombay Lecture series, Swaminathan Gurumurthy (videos).

4. Hind Swaraj, Mohandas K. Gandhi, 1909.

5. Interview with John Galbraith, Outlook India, 2001.

6. Trust: The Social Virtues & The Creation of Prosperity, by Francis Fukuyama, 1995.

7. Social Capital and Civil Society, by Francis Fukuyama, The Institute of Public Policy, George Mason University, 1999.