By Prakruti Prativadi

(About the author)

Bharatanāṭyaṃ conjures images of statuesque dancers, adorned in fragrant flowers and beautiful temple jewelry, wearing vibrant costumes made from the finest sarees dancing to melodic classical Indian music. The dancer pays homage to the Divine, dances in fast rhythmic movements consisting of complex patterns and portrays characters from the many grand epics. The audience is charmed, stirred, entertained and may even recall the performance for some time afterward. Those discerning audience members will recognize the stories and characters portrayed in the dances. Some connoisseurs might delight in the rare Rāgams of the songs or an unusual composition in the repertoire. Others might appreciate the challenging foot movements (Nṛtta) or the dancer’s expressive portrayals (Abhinaya). And yet others may like the subtle interpretation to a venerated classic. There is something to delight in for everyone and unfortunately, for most people, these prosaic features are the totality of Bharatanāṭyaṃ. Experienced Bharatanāṭyaṃ dancers and teachers may understand the subtler aspects of the performance, but for the most part, the very cornerstone of the art is only grasped by few.

In recent years, Bharatanāṭyaṃ has seen an extraordinary increase in popularity and presence, both in India and globally; it is danced by a diverse group of people, throughout the world, from wide-ranging educational, linguistic, racial, religious and economic backgrounds. Ironically however, the understanding of the dance, its fundamental aim, origins and core philosophy has almost reached a nadir. Hailed as a beautiful dance of vibrant costumes and statuesque movements, the very soul of Bharatanāṭyaṃ is not seen or comprehended by many. Bharatanāṭyaṃ is often relegated as just another art form, a medium in which to voice opinions, or as a simple ritualistic dance of temples. Much confusion and misinformation persist among practitioners and teachers themselves, and among the public. The history of Bharatanāṭyaṃ also is often misunderstood and wrongly bears the mantle that it had to be reformed and many erroneously believe that the current dance of Bharatanāṭyaṃ is a sanitized form of a previous version.

Bharatanāṭyaṃ is much more than just a traditional ethnic dance. Bharatanāṭyaṃ embodies the thought system, profound philosophy and practice of an ancient and sacred art originating from a few millennia ago in India. The performance of Bharatanāṭyaṃ is akin to a type of Yoga and is a form of embodied knowing. There is a definite aim in Bharatanāṭyaṃ. It is not just a performance art that is limited to evoking beauty and creating a pleasant experience for the audience. The aim of Bharatanāṭyaṃ is to elevate the audience to experience a higher state of consciousness. To go above the mundane, limited world and realize a greater reality is a fundamental (and unique) concept in Hinduism. Much as Yoga is not just a series of stretches and is a systematized practice, called Sādhana, in which the practitioner aims to achieve a higher state of consciousness, Bharatanāṭyaṃ is also a systematized artistic Sādhana, in which the artist aims to achieve a higher state of consciousness and evoke this state in the audience, so that they can experience it as well. The dancer does this through the dance, the dance steps and the emotive portrayals and storytelling.

Origin of Indian Dance

To comprehend the essence of Bharatanāṭyaṃ and Indian aesthetics, one needs to step back and view this art from within the frame of reference of its origin – Hindu philosophy. Without this point of view, Bharatanāṭyaṃ will not be understood and will be reduced to a mere materialistic art. The Nāṭyaśāstra, written more than 2500 years ago, by Bharata, is the oldest extant treatise on dramaturgy, dance and music and still is the authority today. This treatise meticulously details, classifies and expounds the deep-rooted thought system, practical application, the fundamental purpose and nuance of Indian classical dance. All the extant classical dances of India (i.e. the Desi styles) are living manifestations of the Nāṭya described by Bharata in his Nāṭyaśāstra. The reason they have lived on for more than a few millennia is due to the enduring Dharmic root from which they emerged. The Nāṭyaśāstra is not a mere instruction manual, but a monumental work, in which Bharata connects the art of movement of the body to the mind, intellect and most significantly, to the human consciousness. These are not just Bharata’s own musings however, but a genuine representation of Indian aesthetics which is deeply enmeshed with Indian philosophy and thought. Bharata referenced earlier Hindu works on dance and drama to compile the Nāṭyaśāstra. As explained by Bharata, the stage, the artist and the audience are all unified in this artistic experience. Many treatises have been written about Indian classical dance after Bharata, but they all are based on his work.

Bharata makes it very clear in his work, that Indian dance, drama and music all derived from the Vedas and therefore represent the thought system and knowledge of the Vedas. He states in the Nāṭyaśāstra that by taking the recitative aspect from the Ṛg Veda, music from the Sāma Veda, Abhinaya (enactment) from the Yajur Veda and Rasa from the Atharva Veda, a fifth Veda called Nāṭyaveda was created (Nāṭyaveda refers to the practice and theory of drama, dance and music).

Furthermore, Bharata states that Nāṭyaveda was created to nurture and uphold Dharma:

“(Nāṭya) teaches Dharma to those who are against it, gives relief to those who are afflicted or overtired, brings determination to the sorrowful, enlightens those with poor intellect, brings courage to the cowardly, gives enthusiasm to the heroic, teaches love to those who are eager for it, rebukes the ill-mannered, promotes will-power in the disciplined, gives diversion to the noble and brings happiness, good counsel and knowledge to all.”

By Bharata’s explanation we see that Nāṭyaveda is a manifestation of the knowledge in the Vedas and is a complete experience that involves more than just providing entertainment or a worldly diversion to the audience. Indian dance was created to give knowledge of Vedic principles and benefit everyone in society. Significantly, we see that Indian dance is not just for the elite or the rich, and certainly not reserved only for connoisseurs, but is for the enjoyment and advantage of everyone from all parts of society. The dance is a transformative experience, like all Hindu customs and rituals. There is a definite aim in all Bharatanatyam performances.

Rasa

“There can be no meaningful communication without Rasa” – Nāṭyaśāstra

In Bharatanāṭyaṃ and Indian Aesthetics, this aim is Rasa. Rasa does not have a direct translation in English, in this context. In aesthetics, Rasa does not translate to feeling, or emotion or mood. Rasa is a supreme aesthetic experience, a conscious-elevating state that can be experienced by all. Anyone can experience the Rasa state, anyone who is open to it and is a sensitive and attuned spectator (whom Bharata refers to as a Sahṛidaya). Remarkably, Rasa cannot be understood solely in the intellectual and emotional domains. Rasa involves the mind, intellect and consciousness, and must be experienced. The debate about the specifics of Rasa has been going on for millennia by great scholars like Abhinavagupta, Bhatta Nayaka and others. Thus, Rasa is not something that can be simplified and mapped into a one-word translation and the definition resides in the Dharmic world-view. Furthermore, one requires the experience of Rasa to begin to understand what it encompasses and how it applies to Bharatanāṭyaṃ. What is not of debate, however, is that Rasa is paramount. Rasa is not guaranteed in any given artistic work. It is something that must be carefully generated and is born only if meticulously chosen conditions arise in a dance performance.

“Rasa is born (Rasa-niṣpattiḥ) from the combination of Vibhāvas, Anubhāvas and Vyabhicāri Bhāvas.” – Nāṭyaśāstra

Rasa does not exist in isolation; Rasas are the culmination of a complex process that involves the generation of varieties of Bhāvas, which are mental and emotional states that vary depending on the character and circumstance. There are a total of forty-nine Bhāvas consisting of thirty-three Vyabhicāri (impermanent) Bhāvas, eight Sātvika Bhāvas (with Sattva) and eight Sthāyi (permanent) Bhāvas. Rasa is born as result of all these beautiful Bhāvas – the Vibhāvas (determinants), Anubhāvas (consequent reactions), Vyabhicāri, Sātvika and Sthāyi Bhāvas emerging first. The organic and natural coming together of these results in the birth of Rasa in the onlooker (audience). It is not an afterthought or an automatic outcome. So, viewing a sad story does not necessarily mean the Karuna (pathos) Rasa is experienced. And viewing a comic story does not necessarily mean that Hāsya (humor) Rasa resulted. Thus, just having a Padaṃ or Varṇaṃ about a Nāyikā (female protagonist) does not necessarily mean that the audience experienced the Śṛṅgāra Rasa. The dancer must generate these Bhāvas and Vibhāvas in a genuine manner so that Rasa is born. The subject and themes she chooses to do this are of supreme importance. The limited-self disappears to reveal the more pervading Self – a key element in Hindu practices. Rasa is permanent; it touches and elevates your consciousness. The best part is that you experience Rasa by tuning into the performance, with an open mind and without any preconceived biases. That is why Bharata emphasizes that a Sahṛidaya is best suited to experience Rasa. A Sahṛidaya can be anybody who is a sensitive and attuned spectator, an open-minded and unbiased onlooker, and is not the same as a connoisseur. A connoisseur may be a Sahṛidaya but a Sahṛidaya need not be, and in most cases probably is not, a connoisseur. Significantly, one need not know any technical aspects of the dance in order to experience Rasa.

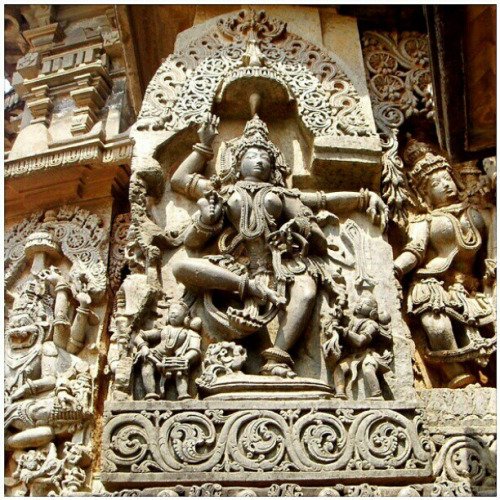

Originally, even the dance foot and hand movements called Karaṇas and Aṅgahāras (analogous to Aḍavus and Jatis of Bharatanāṭyaṃ) produced Rasa. Thus, Rasas should be generated by every aspect of the dance, not just the Abhinaya (expressive enactment) but also by Nṛtta (the rhythmic foot and arm movements). Bharatanāṭyaṃ is a dance of invoking the Divine and was performed, though not exclusively, in Hindu temples as part of the temple rituals. But Hinduism explicitly holds that the Divine is within all of us, so the Raṅga, or stage, becomes a sacred place as well.

Abhinaya and Rasa

Abhinaya is not just the ordinary enactment of stories and characters but the exalted, idealized and glorified re-enactment of stories and characters. This re-enactment generates Bhāvas and Rasas which are readily received and experienced by the Sahṛidaya. By watching the re-enactment of these stories and characters, which are carefully chosen and which enact the four Puruṣārthas of Dharma, Artha, Kāma and Mokṣa, the audience is removed from their mundane day-to-day troubles and problems. The audience forgets the petty limited everyday world and experiences something greater, a limitless Self where the ego disappears and a permanent innate joy is experienced. Hinduism recognizes that this limitless Self and joy is innate and resides in all of us. The dancer must, in effect, disappear from the performance, her ego must not be apparent. For instance, a dancer cannot effectively embody Ānḍāl or dance the Vāriṇaṃ Āyiraṃ without shedding her own persona. The dancer’s petty egos, problems and grievances cannot be visible in such a performance since, if it were, the performance would not be able to produce the desired Rasa experience in the onlooker. Indian dance has survived for millennia because of this unique characteristic. Indian aesthetic theory is unique in that the Rasa concept does not have parallels in aesthetic theories of other world cultures.

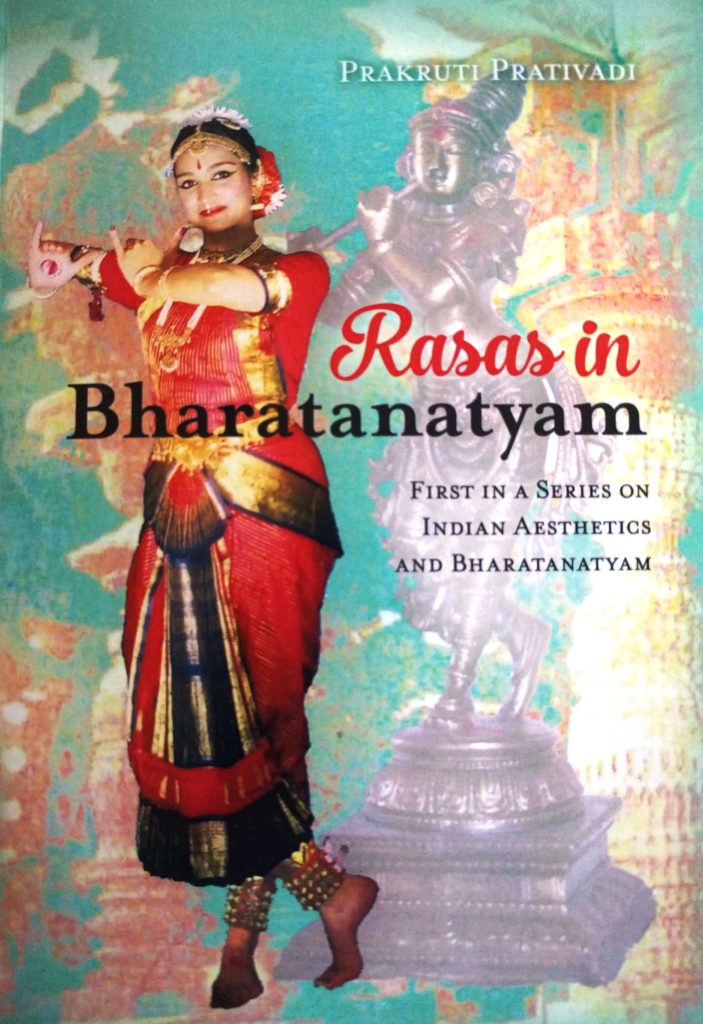

The author dancing selected Pāsurams from the Vāriṇaṃ Āyiraṃ

Rasa is of such significance, that Bharata himself declared: “There can be no meaningful communication without Rasa.” Rasa cannot be an afterthought and it cannot be taken for granted in a performance. The challenge to the artist is to be able to produce this Rasa experience for all members in their audience in their performances.

True scholars of Indian aesthetics like Abhinavagupta have commented that Rasānanda (Rasa bliss experience) is akin to Brahmānanda (bliss of Brahman knowledge). Thus, Rasa is not trivial nor commonplace. Every single element of the dance, including the music Rāgas, Tālas, Aḍavus and even the dancer’s costume, makeup and accessories all come together to generate the Rasa experience.

Many may wonder why the Bharatanāṭyaṃ dancer projects the Dharmic view? After all, Bharatanāṭyaṃ is an art, and art has no religion. Certainly, a paintbrush and paint have no religion. But Bharatanāṭyaṃ is not a lifeless instrument like a paintbrush. Bharatanāṭyaṃ, and all Indian Nāṭya, is a vibrant systematized practice, a sincere Sādhana. It is not a mere vessel in which to voice any capricious view. Bharatanāṭyaṃ is a manifestation of the thought and knowledge of the four Vedas, and therefore, the dance intrinsically carries that world view. Syncretically trying to fit personal viewpoints, incompatible theories and politics into the Bharatanāṭyaṃ repertoire only results in a short-lived forgettable experience, with no Rasa to sustain it.

The responsibility of understanding the rich and sophisticated aesthetic theory manifested in Bharatanāṭyaṃ lies squarely on the shoulders of the dancers, dance teachers and propagators. The audience is not and cannot be expected to study these concepts, but the dancers, by having a well-rounded view, should reflect these in their dances.

Does this mean that the dancer is somehow limited in their artistic expression? No, since the literally innumerable permutations and combinations of facial, arm, hand, leg and body movements included in the Nāṭyaśāstra along with forty-nine Bhāvas and nine Rasas provide for countless variety and diversity of thought and ideas that can be portrayed by an innovative and imaginative artist, all while keeping the ultimate purpose of this great art in mind.

Thus, Bharatanāṭyaṃ is not just an art for art’s sake, nor is it a vehicle in which the artist expresses constrained and personal opinions. Indian dance is elevated, exalted and derives from the Vedas and therefore, reflects the wisdom of the Vedas and like the Vedas, seeks to uplift the consciousness of the onlooker.

Understanding the meaning and purpose of Bharatanāṭyaṃ will make it more accessible to all people, not just a chosen few. It will make it more enjoyable even to those who may not be aware of all its technical merits. And this is indeed a great thing. Because, this characteristic is the reason Indian dance has lasted for several millennia and will continue to endure for millennia to come. In other words, just as the illustrious Bharatamuni envisioned, by understanding and putting to practice the purpose of Bharatanāṭyaṃ, it becomes more reachable, beneficial and enjoyable to everyone.

About the author

Prakruti is the founder director of Kala Saurabhi Dance School in the US and she actively performs in the US and in India. Prakruti is also trained in Carnatic music and is fluent in Sanskrit, Tamil and Kannada. She has spent seven years researching Sanskrit texts and other ancient treatises on Indian art and aesthetics. She has written a book based on her research, Rasas in Bharatanatyam, available at amazon.com.

References:

Ghosh, M.M. 2006. P. Kumar (Ed.) Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharatamuni. (Vols. 1-4). Delhi: New Bharatiya Book Corporation.

Prativadi, Prakruti. 2017. Rasas in Bharatanatyam. South Charleston: CreateSpace.

Sarangadeva, Sangītaratnākara. Adyar Library Series.

Srinivas, P. N. 2000. Mathugalu [Talks on Kannada Literary Criticism, in Kannada]. Bangalore: Purogami Sahitya Sangha.

Subhrahmanyam, Padma. 1979. Bharata’s Art Then and Now. Bombay: Bhulabhai Memorial Institute; Madras: Nrithyodaya.

Subrahmanyam, Padma. 2003. Karanas Common Dance Codes of India and Indonesia (Vols 1-3). Chennai: Nrithyodaya.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1997. The Square and the Circle of the Indian Arts. New Delhi: Abhinav

Publications.

Copyright: Prakruti Prativadi. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer

This article represents the views of the author, and is not necessarily a reflection of the views of the Tamizh Cultural Portal. The author is responsible for ensuring the factual veracity of the content, herein.