"அன்று இரவு கண் துயிலார்

புலர்ந்து அதற்பின் அங்கு எய்த

ஒன்றியணை தரு தன்மை உறு

குலத்தோடு இசைவு இல்லை

என்று இதுவும் எம்பெருமான் ஏவல்

எனப் போக்கு ஒழிவார்

நன்றுமெழுங் காதல் மிக

நாளைப் போவேன் என்பார்."

– Sekkizhar, Periyapuranam [4].

Introduction

Nandanaar, the peerless Siva Bhakta is worshiped as one of the sixty-three Naayanmars (Naayanars) in Tamizh Nadu. His life story is recounted in 37 Tamizh stanzas in the திருநாளைப் போவர் நாயனார் புராணம் as part of the hallowed Periyapuranam of Sekkizhar (சேக்கிழார்) composed in the 12th century. These uplifting verses capture the deepest of human emotions and dharmic ideals and never fail to touch our Atma. The puranam of ‘Thiru Naalai-ppovaar Naayanar’ takes us to the very roots of Sanatana Dharma. Let us recall with reverence our Naayanars and Alvars who ensured that our Kalacharam, Dharma, and Tamizh Mozhi flourish in Bharatam to this day.

Biography

Sekkizhar’s verses on Nandanaar start by describing the prosperity of the town of Aaathanoor (ஆதனூர்) in Melkanadu (மேற்காநாட்டு) of the Chola country whose fertile lands are irrigated by the pristine waters of the Kollidam river. The Pulaiyar community lived in the outskirts of this town in thatched huts. They were farmers, agricultural workers, and leather craftsmen. Sekkizhar describes the different kinds of trees that grow there and talks about the daily activities of the men, women, and children who lived there. In this community was born Nandanaar. From a very young age, he continually meditated on Siva even as he engaged in the profession of leather craft he inherited.

"He came to be born with the continuum of consciousness Of true love for the ankleted feet of the Lord; He, the peerless one, called Nandanar, flourished In that slum of Pulaiyas; he was entitled To the hereditary rights of his clan." - A translation of Periyapuranam [2].

Nandanaar met his basic needs from the money given by the town for his services as the ‘town-crier’ who beats the drum and makes announcements. He gave up all worldly desires and dedicated his life to the worship and service of Siva. His leather-work profession was performed entirely as a Seva to all the nearby temples. For their Pooja, he provided Gorochanai. For their drums and other musical instruments, he provided the leather covers, animal skins, and binding straps. For their Veenas and the ancient stringed Tamizh instrument, the Yazh, he produced the various animal ‘guts’ derived from their intestines.

When we perform actions selflessly, it will eventually result in a pure mind. Through this, the ultimate awareness “I am Siva” rises. Along with that, the harmony of Nature is also preserved. – #Amma pic.twitter.com/ncWF6fPJhj

— Mata Amritanandamayi (@Amritanandamayi) March 5, 2020

Yet this enlightened and most humble devotee of Siva would not enter any of the temples he served with great devotion lest his ‘low birth’ desecrate the temple traditions. He would visit a temple carrying his leather straps on his back, and stand outside the entrance trying to catch a glimpse of the deity. He would then dance and sing songs in praise of Siva and return home to continue his seva.

Once Nandanaar meditated on the feet of Sivalokanathan, the deity at Tirupoonkur and drawn to that deity, he decided to visit the temple. There he sang songs in praise of Siva and pleaded with him so he could get a direct glimpse of the divine he had worshiped for long but had not yet fully seen. The large Nandi of the Siva temple there that faces the deity blocked his direct view. Sivalokanathar commanded Nandi to move aside so his devotee could have his darisanam. Overjoyed, the Siva Bhakta sang songs in praise of Siva. Next, Nandanaar eyed a depression in the land next to the temple, and proceeded to excavate a water tank for the service of the temple. He then performed a pradakshina (circumambulation) of the temple before taking his leave.

Since Nandanaar's visit, the large Nandi in Tirupoonkur sits slightly aside.

Saint Nandanaar eventually visited and served all the nearby temples in this manner. Over time, the desire to see and worship the magnificent Nataraja at Tillai (Chidambaram) with his own eyes grew. He contemplated this night and day and the intensity of his devotion and love for the deity grew. This most sacred of spaces was managed by the ‘three thousand servitors’ (தில்லை மூவாயிரம்) who bound themselves completely to Tillai in the service of the same deity that Nandanaar wanted to behold and worship. Sekkizhar’s Periyapuranam praises the Dikshitars, who are compared to the Ganas of Siva.

Every night, Nandanaar would remain awake and meditate on Siva as Nataraja and every morning, he would decide against going to Chidambaram that day. The Tamizh verses describing the inner conflict and anguish of the Bhakta will melt even the hardest of heart:

அன்று இரவு கண் துயிலார் புலர்ந்து அதற்பின் அங்கு எய்த ஒன்றியணை தரு தன்மை உறு குலத்தோடு இசைவு இல்லை என்று இதுவும் எம்பெருமான் ஏவல் எனப் போக்கு ஒழிவார் நன்றுமெழுங் காதல் மிக நாளைப் போவேன் என்பார்." - [4]. He would not sleep during night; when day broke He would think thus: “My low and inferior birth Will not suffer my adoring at that holy shrine; Even this thought comes to me by my Lord’s fiat.” Thus thinking he would smother all attempts of visit; Yet when nobly-bred love increasingly importuned him He would say: “I’ll go to-morrow.” - [2].

Nandanaar’s distress regarding his birth and Kulam (clan/community) barring his spiritual union with Nataraja is brought out in multiple verses [4]:

- “ஒன்றியணை தரு தன்மை உறு

- குலத்தோடு இசைவு இல்லை” – 21

- “மடங்கள் நெருங்கினவும் கண்டு

- அல்கும் தம் குலம் நினைந்தே”- 23

- “இன்னல் தரும் இழி பிறவி இது” – 27

Through this unending tussle every night and day, he became known as ‘Thiru Naalaippovaar’ (he who would go tomorrow). And then one day, his love for his lord prevailed and he set out for Chidambaram and made it as far as the outskirts where he could see the smoke rising from the sacrificial fires of the Dikshitars in the town. He could hear them chanting the Vedas. He imagined the inside of the fortified town as it had been described. He knew the sacred mathams were nearby and remembered his kulam and ‘low’ birth and did not go further. He went around the town in circles for days and nights wondering when he could catch a glimpse of Nataraja. Nandanaar’s conflict had merely relocated closer to Tillai; his worldly identity could not move any further toward his deity and nor would the true enlightened self consider retreat. Finally, the Supreme deity of Chitrambalam reached out to his Bhaktas.

“This (my wretched birth) is sure the clog.”

Thus thinking he slept; the gracious Lord

Of the Ambalam sensed his distress and to end

All the miseries of the aeviternal servitor,

He appeared in his dream with a gracious smile. ” – [2]

“The gracious Dancing Lord now chose to allay all the sorrow of His devotee. With a gentle smile playing on His lips, He spoke: “To get rid of this birth, you may enter the flaming fire and emerge hallowed in the company of those wearing the three-stranded sacred thread.”” – [1].

The Vedic Brahmanas of Tillai were struck with fear hearing the command of Siva to prepare a fire for Nandanaar. With only Siva in his thoughts, Nandanaar entered their fire without hesitation and emerged unscathed to everyone’s joy. The apparent duality dissolved and the true self beyond limited identities was revealed. He arose from the fire as a ‘Marai Muni’, a self-realized Vedic sage who has experienced the truth of the Shruti. Everyone in Tillai bowed in reverence and adoration. Nandanaar, followed by the assembly, proceeded into the temple for the first time and worshiped the dancing deity and thereafter merged into Siva.

“Thus did the Lord out of His grace, cut asunder the bonds of all ‘karmas’ of the devotee and made him delight for ever in the bliss of His Lotus feet.” [1].

மாசு உடம்பு விடத் தீயின் மஞ்சனம் செய்து அருளி எழுந்து ஆசில் மறை முனியாகி அம்பலவர் தாள் அடைந்தார் தேசுடைய கழல் வாழ்த்தித் திருக் குறிப்புத் தொண்டர் வினைப் பாசம் உற முயன்றவர்தம் திருத் தொண்டின் பரிசு உரைப்பாம் - [4]

Humbled was the ego of those among the guardians of Tillai who could not see Siva within Nandanaar. The final act establishes the inner fire of spiritual purity as supreme and brilliantly inverts the meaning of ‘untouchable’ in the case of Nandanaar who was beyond mortal desires:

“An unexampled exception in the mode of worship was made by the Lord in the case of Nandanar, the untouchable. Yes, he was an untouchable and no evil or pollution could ever touch him. The Lord demonstrated to the world the fact that he was even greater than the Tillai Brahmins“- [2].

Thus ends the mortal portion of the story of Thiru Naalaippovaar Nayanaar documented in the Periyapuranam. Nandanaar lives forever as one among the 63 Nayanmars whose Murthis grace multiple prominent Hindu temples including the Meenakshi Amman Kovil in Madurai.

Periyapuranam

The Periyapuranam is the twelfth among the twelve devotional Stotram canons (Panniru Tirumurai) in the Tamizh Saiva tradition and consists of 4253 verses. Its author Sekkizhar was a contemporary of Chola king Anapaya (Kulathunga Chola-2) who was a great devotee of Nataraja at Chidambaram. Sekkizhar authored the Periyapuranam in the 12th century and called it the Thiruthondar Puranam, the Sacred Anthology of the Servitors of Siva. The main purpose of reading or listening to these verses is the purification of one’s mind (Chitta Shuddhi). Sekkizhar expanded upon the prior work Thiruthondatthohai of Sundarar (one of the divine trinity of Saivite Saints that includes Appar and Sambandar) in the 8th century, followed by Nambiyaandaar Nambi’s Thiruthondar Thiruantadi in the 11th century.

As Sundarar’s original work only provided a brief summary of the Nayanaars, Sekkizhar visited all the locations associated with the Nayanaars and studied the inscriptions and other material to document an authoritative and more detailed account of their lives and contributions. Ramana Maharishi‘s spiritual journey was inspired by his reading of the Periyapuranam at a young age:

“Towards the end of 1895 (perhaps a few months after hearing about Arunachalam from a relation) he found at home a copy of the Periya Puraanam which his uncle had borrowed. This was the first religious book that he went through apart from his class lessons and it interested him greatly…. It transported him to a different world…. ”

The 63 Nayanmars in the Periyapuranam come from all sections of the society and include both women and men. Nandanaar was a leather worker whose raw materials were the carcasses of domestic animals, while Thiru Neelakanta Naayanar was born in a potter clan. The revered Saint Kannappan was a hunter, while several others were vendors, merchants, priests, kings, soldiers, etc. All are recognized as Jivanmuktas who had gave up all worldly desires to seek refuge at the feet of Siva [1]. Each of their life stories are remarkable and teach us lessons in self-realization and dharma. In the case of Nandanaar whose Siva-Consciousness was evident from an early age, it was not only about Mukti but also about Nataraja imparting a valuable and timeless lesson to devotees.

Later Narratives

Sri Gopalakrishna Bharathi, a great composer of Carnatic Sangeetam came up with an operatic musical version, the Nandana Charitram in the 1860s. This work is recognized for its highest musical and lyrical quality. However, Sri Bharathi introduced imaginary events inspired by the social-political churn in British-occupied India. Few doubted the reformative intent of Bharathi and this part-fictional version became popular all over India through Carnatic compositions, Bharatanatyam recitals, Harikatha, and feature films. An interesting story of Bharathi’s work and its critique by the renowned scholar, Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai is recounted here [3].

It should come as no great surprise to contemporary readers that this version has been seized upon by western academia and politicians for its ‘Breaking India’ propaganda value. Using a western lens, Itihasa is dismissed as mythology and Periyapuranam is reduced to hagiography. In this framework, the spiritual context, the transcendental nature of the millennium-old story of dharma, the seva and tapas of Nandanaar, and the central idea of Siva Bhakti are either distorted or discarded. Instead, speculative and divisive commentaries totally contrary to the Periyapuranam are produced.

Nandanaar’s Legacy

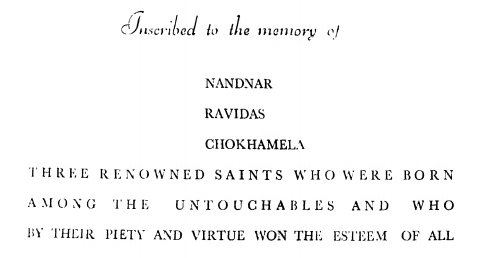

The life of Nandanaar as told by Sekkizhar brings to mind other sacred stories from our Itihasa and Puranas including Bhakta Prahalad who emerged from the fire unscathed while the ‘fireproof materialist’ Holika did not; we find parallels in the life of Bhakti saint Mira who overcame many barriers and ultimately merged into Krishna. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s book on The Untouchables is dedicated to a trinity of Hindu saints [7]: Nandanaar, along with Sant Chokamela, the great devotee of Vithoba from Maharashtra, and Sant Ravidas the disciple of the Vaishnava Saint Sri Ramananda, and the guru of Mira.

The Chidambaram temple where Nandanaar Muni merged into Siva has endured many trials and violent attacks in the last millennium and has emerged stronger each time. The Dikshitars have protected the Tillai deity throughout history and many gave their lives defending the temple against a barbaric assault by Malik Kafur in 1310-11. The temple became one of the first to welcome people from all sections of the society to worship Nataraja. The Dikshitars continue their millennia-old hereditary tradition of serving the Tillai deity despite severe economic and social hardship [5].

Today, leather workers in India can not only set up thriving businesses, they are leaders of the Samaj who inspire and support others in distress. Such achievements have been recognized by the Indian Government, and by the Prime Minister’s ‘Mann ki Baat’ social media handle on Women’s day.

Rupali Shinde transformed her caste occupation of treating the carcass of dead animals into a thriving business in leather based musical instruments. She mentored 1,000 drought affected women to start their own ventures and is known as ‘Rural Digital Guru’. #SheInspiresUs pic.twitter.com/ZVOQx0upx1

— MyGovIndia (@mygovindia) March 7, 2020

Ultimately, the story of Nandanaar is a celebration of Sanatana Dharma and its fundamental principle of harmony and well-being of all barring none.

References

- Saint Sekkizhar. Periyapuranam. Sri Ramanasramam. 2013.

- Shaivam.org: The Puranam of Tiru Nalai-p-povar – Periyapuranam as English poetry.

- Nandanar: the imagination that won over truth. 2008.

- Shaivam.org: 12.024 திருநாளைப்போவார் நாயனார் புராணம்.

- http://www.chidambaramnataraja.org/deekshithar.html.

- HinduismToday: A Priestly Clan Under Siege. 2009.

- Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. The Untouchables: Who They Were And Why They Became Untouchables? 1948.