By Prakruti Prativadi

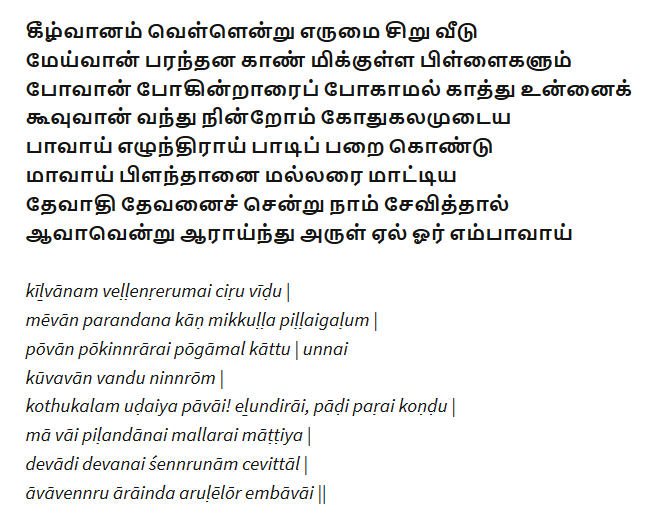

Meaning of above pāsuram – “Dear girl, who is full of utsāha and dear to Śrī Kṛṣṇa, please come and join us. The eastern sky is light and it is dawn, the buffaloes are grazing on tender dewy grass. We and other gopī-s were on our way but have delayed our vratam and are here waiting for you, so that you too may join us. Please awake so that we can all sing of the greatness of Śrī Kṛṣṇa and when we approach Him, the One who destroyed the asura Keśi and the wrestlers of Kamsa’s court, Śrī Kṛṣṇa, the God of Gods, will evince great interest in our welfare and through His dayā, will remove our deficiencies (so that we can attain mokṣa)”.

This beautiful verse is one of thirty pāsuram-s (sacred verses) spontaneously sung by Āṇḍāḷ (Gōdai or Godādevi) as part of her composition, the Tiruppāvai, when she was eight years old. This pāsuram is a call from gopī-s who are in a state of enlightenment granted by Śrī Kṛṣṇa. They are enlightened as to what true bhakti is, which is above bodily desires. Āṇḍāḷ visualizes the gopī-s in that state of pure bhakti which is a prerequisite for attaining moksha. Āṇḍāḷ shows concern for all devotees and exhorts them to awaken and join her and these enlightened gopī-s in the vratam that will culminate in receiving jñāna and dayā of Śrī Kṛṣṇa. Furthermore, as Ācārya-s have stated, the gopī Āṇḍāḷ awakens actually represents one of the enlightened Āḻvār-s; Āṇḍāḷ requests this Āḻvār to join the vratam and share his Vedic knowledge with other devotees so that they too can benefit. Āṇḍāḷ sang these sacred pāsuram-s as a spontaneous outpouring of her supreme bhakti which ultimately culminated in her attaining mukti. These sacred songs are rooted in the Veda-s, Upaniṣad-s and Bhagavad Gīta with the knowledge of these is embedded in each pāsuram.

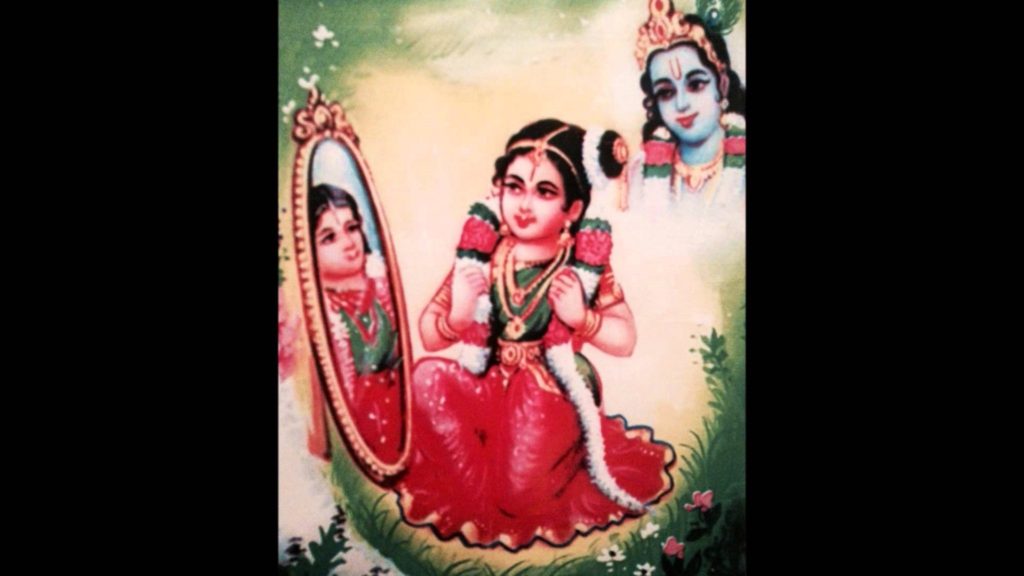

Āṇḍāḷ

Artwork and Copyright by P.N. Srinivas

As Āṇḍāḷ has stated, her sacred songs and the practice of the accompanying vratam are sāttvik in nature and are meant for those who wish to acquire sāttvika guṇa-s. Āṇḍāḷ achieved mokṣa around the age of nine years when she merged and became one with the mūrti of Śrī Raṅganātar at the Śrī Raṅgam Temple. She is honored by women and men, girls and boys who continue to fulfill her vratam and seva. Āṇḍāḷ is extraordinary because she had a pure, innocent, and sāttvik mind. She was born with great bhakti for Śrī Kṛṣṇa, her pāsuram-s are a reflection of her pure sāttvika bhakti that she experienced as an 8 or 9-year-old child and wished to share with devotees. In studying Āṇḍāḷ and her life, it is important that adults do not impose their own speculations, viewpoints, limitations, or wishes onto the child Āṇḍāḷ’s sāttvik works. As Śrī Kṛṣṇa Himself states, everyone is born with different guṇa-s and differing levels of bhakti; and Āṇḍāḷ by all accounts was an extraordinary child and bhakte operating at a higher level than the laukika world and higher than the limited view of even other devotees.

Āṇḍāḷ

Āṇḍāḷ has achieved an exceptional and reverential status in the hearts of Indians and within Hinduism. Though her works are in Tamiḻ, Āṇḍāḷ crosses the barriers of gender, language, regions, cultures, and varṇa-s, and cuts across social and economic distinctions. Āṇḍāḷ is often erroneously described as a woman, she in fact was a young girl. This important detail is significant because it facilitates understanding of her pāsuram-s from the correct viewpoint and also because it is a fact that is obscured and misrepresented in academia, media, and the general public. As a child, Āṇḍāḷ spontaneously composed two major sacred works dedicated to Śrī Kṛṣṇa and she initiated a month long vratam during the month of Mārgaḻi (Mārgaśīriṣa). Her most important contribution is the seva she did by sharing her knowledge of Vedānta with everyone so that they may benefit. The two compositions, the Tiruppāvai consisting of thirty pāsuram-s, and the much larger sacred work, the Nāciār Tirumoḻi, consisting of one hundred forty-three pāsuram-s, became part of the Nālāyiram Divyaprabhandam which is the works of all the Āḻvār-s (including Āṇḍāḷ) and recited in all Śrī Vaiṣṇava temples, festivals, and pūja-s. Āḻvār-s belong to the Śrī Vaiṣṇava sampradāya, which embraces the Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta darśaṇa in Hinduism. Significantly, the Āḻvār-s came from different varṇa-s and many were not Brahmin. There are twelve Āḻvār-s, Āṇḍāḷ being the only girl. Though she belongs to the Śrī Vaiṣṇava sampradāya, followers of other sampradāya-s also practice the vratam Āṇḍāḷ established and recite her pāsuram-s. Because of her exceptional life and contributions, Āṇḍāḷ is considered an avatāra of Bhūdevi tāyār and thus, in temples her mūrti is depicted as a grown woman, though Āṇḍāḷ was only 9 years old at the time she achieved mokṣa at the feet of Śrī Raṅganātar.

Āṇḍāḷ

Artwork and Copyright by Prakruti Prativadi

Though just a young child, Āṇḍāḷ commands both respect and adoration and she naturally attained a timelessness that few others possess. This status was not just accorded to her, she rightfully achieved this position through her ageless sacred compositions and through the example she set by living the principles illustrated in her pāsuram-s. Her life itself was a tapas, culminating in her gaining mukti from the eternal cycle of re-birth. Āṇḍāḷ was only around eight or nine years old when she finished her two sacred works: the Tiruppāvai and the Nāciār Tirumoḻi, and around the same age attained mokṣa at the feet of Śrī Raṅganātar in the temple at Śrī Raṅgam. Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s have nothing to do with the “coming of age”, which is a mundane dumbing down of her incredible contribution; nor can their meanings be taken literally. As seen in the above pāsuram, the compositions contain much symbolism and are pointers to deeper Hindu metaphysics.

As Āṇḍāḷ herself has stated in the Tiruppāvai, her works are meant for those who wish to become more sāttvik and attain sāttvika guṇa-s; thus, rendering the rajasik and laukika interpretations of the Tiruppāvai and Nāciār Tirumoḻi fallacious and deceptive. Many people erroneously think Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s are about worldly love, they often corrupt the meaning of Āṇḍāḷ’s compositions because they see it through their own limited worldly view. The pāsuram-s of the Nāciār Tirumoḻi and Tiruppāvai speak to an elevated state of consciousness; they were composed by a pure-hearted young child who was born with bhakti that was already far advanced of all others. It is difficult for the ordinary mind to really understand and experience her works, however, even to attempt an understanding of her compositions we must elevate our own state of consciousness and view Āṇḍāḷ and her works with the correct dṛiṣti. Arjuna could not experience the Viśvarūpa until Śrī Kṛṣṇa gave him divya dṛiṣti, the Paramātma can only be perceived through the antaścakṣu, and similarly, Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s cannot be experienced without the sāttvika state of consciousness. One ultimate purpose permeates throughout her songs: the jīvātma striving to unite with the Paramātma thereby attaining mokṣa.

Āṇḍāḷ is accorded the position of Āḻvār among the Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s. The Tamiḻ non-translatable word Āḻvār does not have an equivalent in English and means “one who is immersed in (the Paramātma)”. Āḻvār does not mean ‘Saint’. Her pāsuram-s contain the complex sacred knowledge of the Veda-s, Upaniṣad-s, and Bhagavad Gīta in a manner that is accessible and understandable to the lay person. Āṇḍāḷ embodied Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta and the yoga-s of bhakti, jñāna, karma, and further practices like śaraṇāgati and prappati are embedded in them.

In this vratam lasting thirty days, Āṇḍāḷ envisioned her entire village of Śrī Villiputtur as Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s village of Nandagokula in the Dvāpara yuga, and the Vatapatraśāyi temple as Nanda’s house where Kṛṣṇa lived. Such was her bhakti and pure, idealistic mind. Each pāsuram of the Tiruppāvai is dedicated to one day of the vratam, and each pāsuram’s meaning encapsulates profound kernels of bhakti yoga and Vedānta that ultimately lead to the feet of Śrī Kṛṣṇa and mokṣa. Significantly, the pāsuram’s are encoded with poetic language and charming imagery, however that is not the real meaning that Āṇḍāḷ is conveying; she has encoded the pāsuram-s with deep knowledge that one accumulates over lifetimes of tapas. These pāsuram-s also contain picturesque imagery as Āṇḍāḷ gracefully weaves the bustling activity of every day village life into the pāsuram-s. These descriptions represent deeper Vedic principles. Āṇḍāḷ describes the activities of the unpretentious village folk, the men, women, girls, and boys going about their daily activities, and this serves as an important link to our samskṛti and cultural history. Āṇḍāḷ ‘s love of cows is evident in the pāsuram-s; many verses of the Tiruppāvai contain the most striking descriptions of the cherished and nurtured cows of the village and how they generously and bountifully give rich nourishing milk on their own. The cows are lovingly protected and taken care of by the people of the village; cows are an important part of the Hindu ethos and metaphysics, cows symbolize many sāttvik guṇa-s and are a personification of the Veda-s and Upaniṣad-s. This reverence and affection for cows is natural and benign, however, this aspect of Hinduism too is a target for those driven by agendas of bigotry and hatred. Because these pāsuram-s are moving and beautiful, they have been described as poetry however, Āṇḍāḷ’s motivation was not to compose poetry but to share Vedic knowledge and inspire others to do kainkaryam through her songs. This point is significant, merely labeling Āṇḍāḷ’s works as poetry alone denies this visionary young girl her rightful place as a remarkable person and spiritual figure. One cannot comprehend Āṇḍāḷ through reading articles or books or as a mere observer, Āṇḍāḷ can only be understood through sādhanā and tapas under the guidance of a learned Ācārya. This write-up is a mere glancing introduction to Āṇḍāḷ.

Āṇḍāḷ from the natural innate lens:

Like many others, I cannot recall when I first learned of Āṇḍāḷ; just as one cannot recall being first aware of one’s mother, father, siblings, or grandparents. I’ve been aware of her from such a young age that she was simply a part of our family. As a child I thought Āṇḍāḷ lived somewhere nearby and eagerly looked forward to visiting her soon someday, a guaranteed certainty I never doubted – illustrating how seamlessly integrated Āṇḍāḷ and her pāsuram-s are in our daily lives and in our very identities – in a manner that is organic and unpretentiously genuine. Āṇḍāḷ cannot be understood through a worldly laukika viewpoint that even some Hindus employ, or by academic study, or by donning an outsider alien lens; nor can her pāsuram-s be viewed through 20th century lens of postmodernism or feminism. Āṇḍāḷ and her pāsuram-s are comprehended through an innate worldview that Āṇḍāḷ herself described and embodied. Over the years, one learns about her by learning her pāsuram-s and their complex beautiful meanings through the practice of the pūja-s and vratam she prescribed. As with any Hindu practice, and as reiterated by Ācārya-s, it is through sādhanā – the daily practice with śraddhā and bhakti of reciting and putting into practice the practical aspects of Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s, that one can gain insight and ātmānubhāva of Āṇḍāḷ and her compositions. And this was her dearest wish for the rest of us jīvātma-s, that like Āṇḍāḷ, we too would attain the Paramātma and her pāsuram-s would aid us in that ultimate liberation.

The most attractive characteristic of Āṇḍāḷ for me as a child, and for many Hindu children, is Āṇḍāḷ was a little girl, no more than eight years old when she started spontaneously singing her pāsuram-s to the Vatapatraśāyi (Śrī Kṛṣṇa in the form of an infant in yoga-nidra reclining on a Vatapatra leaf). Despite her extraordinary insight, I felt an instant sisterhood with Āṇḍāḷ, a young girl, like me, wearing tilakam, pāvāḍai, bangles, with dark black plaited hair adoring Śrī Kṛṣṇa and His activities, and practicing our everyday customs, gently nudging us to be something greater, to transcend this mundane world and our limited selves. I was amazed by her self-motivation and initiative to do seva and kainkaryam to Śrī Kṛṣṇa and to the ordinary people in her village on her own, selflessly. The details of her life, the happy imagery of her pāsuram-s, her genuine idealism, and all-involved concern for others to share the Vedic knowledge beyond her years instantly makes her a favorite role-model and an indelible part of Indian girlhood. And this is the most significant part of Āṇḍāḷ that is oftentimes completely missed by those who think they can dissect and analyze her through their own narrow viewpoint: Āṇḍāḷ is the essence and spirit of Indian girlhood- she is the quintessential Indian girl.

Āṇḍāḷ’s Life:

Understanding Āṇḍāḷ and her pāsuram-s requires an understanding of Āṇḍāḷ’s life story (the term hagiography does not apply to Āṇḍāḷ and should be eschewed). Āṇḍāḷ lived before Śrī Rāmānujācarya, probably in the 7th or 8th century, though some scholars place the date to several millennia prior. The village of Villiputtur (later named Śrī Villiputtur after Āṇḍāḷ) near Madurai, Tamil Nadu has an ancient and beautiful temple of the Vatapatraśāyi Śrī Kṛṣṇa. Viṣṇu Citta (Peri Āḻvār) was a devout and learned man who lived in Villiputtur and served the temple every day. Viṣṇu Citta is also an Āḻvār and has composed sacred works; during his lifetime he did seva in the temple. One day while digging in the tulasī garden, he found a baby girl and decided to raise her as his own daughter and named her Gōdai (Kōdai or Godādevi), this child would later be known as Āṇḍāḷ. Viṣṇu Citta noted the remarkable similarity of this child with Sita, who was also found in this manner; thus indicating that Āṇḍāḷ was no ordinary child; Āṇḍāḷ is known as ayonije – one who is not born of a womb. The tulasī garden where Gōdai was found still exists today in Śrī Villiputtur. Viṣṇu Citta thought of himself as the personification of Yaśoda and the child Gōdai as Kṛṣṇa, and in this manner, he embodied the Vātsalya bhakti toward the child. He showered her with affection and imparted the knowledge of Vedānta to her and lovingly raised her. Thus, Gōdai grew into a little girl all the while imbibing the knowledge of the Veda-s, Upaniṣad-s, the Bhagavad Gīta, purāṇa-s, and śāstra-s from her father Viṣṇu Citta. She listened with rapt attention to the stories of Śrī Kṛṣṇa; and the precocious child Gōdai would draw pictures of Śrī Kṛṣṇa, his āyudha-s, and episodes from Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s life on the floor and walls of her home. As Gōdai grew she was immersed in the bhakti for Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Viṣṇu Citta finds baby Āṇḍāḷ in the tulasī garden

A famous incident in Āṇḍāḷ’s life revolves around the mālai (flower garland) that Śrī Viṣṇu Citta would send to the temple every day to be adorned on the Vatapatraśāyi at that temple. Flowers are first offered to the Deity before anyone else can wear them, but unbeknownst to Viṣṇu Citta, Gōdai, with her innocent enthusiastic bhakti, would first wear the mālai meant for the Vatapatraśāyi before it was sent to the temple, thus Āṇḍāḷ is referred to as “Śūdikoḍuta Śuḍarkoḍi Nāciār” or the ‘the girl who offered the garland after having worn it’. However, one day, Viṣṇu Citta noticed a strand of hair in the mālai; he was dismayed and told his daughter that the garland must never be worn before it was offered to the Vatapatraśāyi. Later, Viṣṇu Citta had a vision in which the Vatapatraśāyi tells him that only the garland worn and then offered by Gōdai will be accepted. And thus, from then on Gōdai was known as Āṇḍāḷ – ‘the girl who ruled over the Lord’. This charming incident from Āṇḍāḷ’s life illustrates the remarkably oneness Āṇḍāḷ felt with Paramātma even as a young child, and is parallel to Śabari offering fruits, after having tasted them, to Śrī Rama in the Ramayana. Furthermore, this episode is not an example of mundane disobedience or rebellion as some revisionist historians and feminists zealously claim. Rather, the incident of Āṇḍāḷ wearing the garland illuminates several subtleties of Vedānta, one is that the Paramātma accepts the offerings of bhakta-s when these are made with śraddhā, love, and pure bhakti; secondly, Āṇḍāḷ so identified herself with Śrī Kṛṣṇa that, when she wore the garland it was as if she was garlanding Śrī Kṛṣṇa Himself. Remarkably, this event lives on even to this day and is re-embodied in the custom of sending the garland that adorned Āṇḍāḷ in the Śrī Villiputtur Āṇḍāḷ Temple to the Tirupati Tirumala Temple, to adorn Śrī Venkaṭeśvara during the grand Brahmotsavam festivities. Additionally, during the month of Citra Pournami, the garland that adorned the Āṇḍāḷ mūrti in Śrī Villiputtur is sent to the Aḻagar Kōvil during Garuḍotsavam. These are not mere robotic rituals, they personify the union of the jīvātma and the Paramātma which Āṇḍāḷ embodied and shared with others and thus, she is honored today by bhakta-s re-embodying her experience and sharing it with other devotees in the manner she herself wished.

Āṇḍāḷ and the garland (Picture from author’s collection)

Starting at the young age of 8 years (per some scholars she was 5 years old), Āṇḍāḷ composed and sang sacred verses called pāsuram-s, which were replete with references to the Bhāgavataṃ, Bhagavad Gīta and directly refers to the knowledge in the Veda-s and Upaniṣad-s. These pāsuram-s of the Tiruppāvai talk of urging everyone (jīvātma-s) not to waste this precious life and to orient themselves to attain the Paramātma. The pāsuram-s are artistic and poetic. The Nāciār Tirumoḻi, which is a much longer work, also contains this knowledge wherein Āṇḍāḷ embodies the stages of bhakti that a serious sādhaka experiences, which finally culminate in attaining the Paramātma. In the Nāciār Tirumoḻi, Āṇḍāḷ, using much symbolism and imagery, expresses she does not want the body attained in this birth to be wasted in worldly materialistic and laukika pursuits but dedicates this birth to attain mokṣa. Here Āṇḍāḷ puts herself in the place of a bhakta and describes each stage of their tapas.

The Nāciār Tirumoḻi is a grand sacred opus, which is lyrical, mystical, and illuminating. Within it is the Vāraṇam Āyiram, a section describing a mystic vision of Āṇḍāḷ. In this vision, Āṇḍāḷ details how her jīvātma was united with the Paramātma, symbolized as a Vedic wedding. However, this does not mean that Āṇḍāḷ envisioned herself married to Śrī Raṅganātar as is often misinterpreted, and this vision should not be mistaken for a worldly marriage ceremony which would initiate the gṛhastāśrama. The vision described in the Vāraṇam Āyiram is of Āṇḍāḷ attaining mukti and her ātmā attaining the Paramātma; mokṣa is often symbolized in Hinduism as a marriage of the jīvātma and Paramātma. Incidentally, the Vāraṇam Āyiram is recited in the wedding ceremonies today as well, however the mystical ceremony Āṇḍāḷ describes is of her attaining mokṣa. The metaphor of mokṣa in Āṇḍāḷ’s vision in which she (jīvātma) is ‘married’ to Śrī Raṅganātar (Paramātma) is misconstrued as a worldly marriage especially by those donning the laukika or western lens. There is no doubt that the Vāraṇam Āyiram is really the final attainment of mukti by Āṇḍāḷ, who has achieved through her pūrvajanma puṇyakarma, a state of enlightenment which is required to qualify for mokṣa in this birth. This final attainment is often metaphorically described as marriage in other Hindu works as well, especially with respect to bhakti yoga.

Though her pāsuram-s contain abstract and difficult to understand Vedantic knowledge, Āṇḍāḷ encapsulates this knowledge in these pāsuram-s that are accessible to the lay person who sincerely wants to understand them. However, Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s cannot be interpreted by those who do not have a firm rooted ātmānubhāva and technical understanding of the Veda-s, Upaniṣad-s and Bhagavad Gīta. One can only understand the pāsuram-s through an in-depth and consistent study guided by an Ācārya. Her contribution is, her pāsuram-s allow us to put into practice this Vedic knowledge and she shared this wisdom because of her infinite karuṅā (compassion) to her fellow beings so that they too might benefit from this knowledge and attain mukti. Indeed, this impetus propelled Āṇḍāḷ to compose these pāsuram-s – as a seva, a truly unselfish magnanimous act, in which she wanted to share her experience and knowledge with everyone regardless of their status in society and regardless of their gender.

In her young life, Āṇḍāḷ did attain the object of her tapas, with Viṣṇu Citta’s blessings, she arrived at the Śrī Raṅgam temple and stepped into the sannidhi of Śrī Raṅganātar and she disappeared, merging into the mūrti – thus attaining mukti; she was only 9 years old at that time. Āṇḍāḷ’s life story is remarkable due to her simplicity, her magnanimous seva for others, and her one-pointed tapas.

The tulasī garden in Śrī Villiputtur where Āṇḍāḷ was found (source:http://www.cpreecenvis.nic.in/Database/Srivilliputhur_2073.aspx)

For more than 1200 years, Āṇḍāḷ has been honored by both men and women alike, she is considered an avatāra of Bhūdevi, the mūrti of Āṇḍāḷ as Bhūdevi adorns every single Śrī Vaiṣṇava temple including the temples of her hometown Śrī Villiputtur and in Śrī Raṅgam, and pūja is done to her per the śāstra-s. Śrī Rāmānujācarya, the acharya of the Viśiṣṭādvaita sampradāya followed by Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s, had great reverence for her and established that her pāsuram-s should be sung in the Śāttamurai and all major pūja-s. Indeed, all the major Ācārya-s have revered Āṇḍāḷ and her pāsuram-s.

Āṇḍāḷ’s life is one in which she seeks, without pause, mokṣa and for her ātmā to unite with Śrī Kṛṣṇa (Paramātma) during her life to break the cycle of birth and death. Āṇḍāḷ’s most significant contribution is the access she gave of the knowledge of the śṛti-s to everyone, and the example she herself embodied by showing us that these must be shared with others who have śraddhā, bhakti and who are willing to follow the procedures of this sādhanā without injecting their own selfish agendas or motives. Āṇḍāḷ followed the spirit of “eka: svādu na bhunjita”, which means – do not enjoy something by yourself alone. So Āṇḍāḷ’s motivation was to share the joy of Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s anugraha, and to let others also partake of that joy. She did this to help people overcome the sufferings of samsāra and ego and the bondage of karma. Her pāsuram-s are steeped in sattva and are for those people who want to be more sāttvik. In her pāsuram-s, she also describes different kinds of bhakta-s and their experiences. These pāsuram-s are not just capricious musings or self-centered thoughts of a young ‘woman’ as feminists and revisionists seek to make them.

Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s and vratam are not only limited to bhakti, her pāsuram-s are an in-depth exploration of para–bhakti, prappati, para–jñāna, paramā–bhakti and śaraṇāgati.

The 14th century scholar and Ācārya Śrī Prativādi Bhayankaram Aṇṇa has traced and identified the Vedic sources and references to smṛti in the Tiruppāvai and the Nāciār Tirumoḻi.

As the great Jīyar and Ācārya Śrī Manavāḷa Māmuni states about Āṇḍāḷ: – “emakkāga anṛō ingu Āṇḍāḷ avadarittāḷ” which means “She was born to rid us of the misery of the infinite cycle of birth and death – our trudging through the cycle of samsāra.

The great scholar and Ācārya Śrī Vedānta Desikar has composed the Godā Stuti, extolling the greatness of Āṇḍāḷ.

Śrī Rāmānujācarya himself completed a particular kainkaryam (nūrtada, which was mentioned in the Nāciār Tirumoḻi) that Āṇḍāḷ wanted to have done in the Śrī Raṅgam temple.

Śrī Vaiṣṇava Sampradaya and the Significance of Mahālakṣmi

The “bhakti movement” is an unfortunate moniker that only serves to gloss over the profound darśaṇa-s that espouse bhakti yoga as their primary method to mokṣa. The same is true for the term “Vaiṣṇava” which actually comprises of differing sampradāya-s that are all rooted in the śṛti-s but each have their own technical practices and approaches. Bracketing them all under the inelegant terms “bhakti movement” or simply “Vaiṣṇava” is reductionist and contributes to distortions of these rich sampradāya-s. For instance, the four so-called Vaiṣṇava sampradāya-s actually espouse different darśaṇa-s: Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s accept the view of Viśiṣṭādvaita, whereas followers of Madhvācārya, Vallabhācārya and Nimbārka adopt Dvaita, Śuddhādvaita, and Dvaitādvaita respectively. The point here is not that these are divergent, in fact they are all rooted in the Veda-s and Upaniṣad-s, but their unique methods and views should be appreciated and understood, thus preventing misrepresentation and erroneous interpretations. Surprisingly, the moniker ‘bhakti cult’ still sees use, a pejorative characterization first used by Indologists and still employed among some Indians and those adopting the western lens today.

Viśiṣṭādvaita (Viśiṣṭa Advaita – qualified non-dualism) has ancient origins in the Upaniṣad-s and was systematized and organized by Śrī Rāmānujācarya (1017CE -1137CE). Viśiṣṭādvaita has the Veda-s as its authority and reflects the metaphysics of the Veda-s, Upaniṣad-s, itihāsa-s and purāṇa-s. Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s are concentrated mainly in southern India in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana, but there are followers spread across northern India and many in the global Hindu diaspora as well.

As mentioned, Āṇḍāḷ belongs to the Śrī Vaiṣṇava sampradāya and her pāsuram-s indeed refer to many of the principles of the darśaṇa (view) of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta. For instance, in the Tiruppāvai, Āṇḍāḷ metaphorically refers to the five manifestations of Brahman: para, vyūha, vibhava, antaryāmin, and arca.

Significance of Śrī

Of special note, is the status of Mahālakṣmi (Śrī) in Śrī Vaiṣṇava sampradāya in which She holds a special and critical position. Nārāyaṇa and Lakṣmi are one inseparable entity and thus referred to as Śrīman Nārāyaṇa, which means Nārāyaṇa who is always with Śrī. Āṇḍāḷ’s works refer to the significance of Śrī extensively. Mahālakṣmi dwells permanently in Nārāyaṇa’s vakśasthaḷam (chest). This imagery embodies the significant role Lakṣmi has in the Śrī Vaiṣṇava sampradāya. Mahālakṣmi is the puruṣākāra i.e. it is only through Mahālakṣmi’s karuṅā and through Her as facilitator between the jīva-s and Nārāyaṇa that the jīvātma can attain mokṣa. Thus, Mahālakṣmi manifests supreme compassion, is the Universal Mother, and the anugraha śakti of Nārāyaṇa. Mahālakṣmi has three aṃśa-s or manifestations: as Śrīdevi She is the kriyā śakti, as Bhūdevi She is the viṣva śakti, and Nīlādevi She is the icchā śakti. Śrīdevi, Bhūdevi and Nīlādevi are not merely the ‘wives’ or ‘consorts’ of Śrīman Nārāyaṇa, but are inseparable śakti-s. It is an unfortunate tendency of many Hindus to transform our Deities into solely domestic mundane laukika entities, resulting in the loss of understanding their true Vedic spiritual meaning.

Bhakti

The term bhakti has become ubiquitous, often used out of context, and misapplied. Bhakti does not mean devotion or love; the term bhakti seems to have become a catch-all word in describing any type of prayer or worship in Hinduism, especially as interpreted through the non-Dharmic lens. As Āṇḍāḷ’s has illustrated in her works, there are accompanying stages of bhakti that are analyzed by the Ācārya-s. In order to practice bhakti, one must be qualified and must practice the aṣṭāṅga yoga-s. The Viśiṣṭādvaita interpretation and practice of bhakti yoga is complex, vast, and esoteric and beyond the scope of this article. Per Viśiṣṭādvaita, jñāna – karma – bhakti is the natural order of the yoga-s of a sādhaka’s evolution. Therefore, we see that bhakti is not a practice devoid of jñāna and karma. The path to mokṣa per Viśiṣṭādvaita is fivefold:

- karma

- jñāna

- bhakti

- prapatti

- ācāryabhimāna

Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s refer to these stages of bhakti. A practitioner of bhakti yoga also must observe the following:

- viveka (purity and discrimination between right and wrong),

- vimoka (inner detachment)

- abhyāsa (unceasing sādhanā of the presence of the Paramātma as the indwelling Self)

- kriyā (seva to others)

- kalyāṇa (practice of right conduct)

- anavasāda (cheerfulness in life, freedom from complaining and dejection)

- anuddharṣa (not exulting about one’s virtues or achievements)

Most importantly, in these stages, the practitioner seeks to transcend their ego and obliterate it by becoming one with the Paramātma. One’s petty personal viewpoints and egotistic whims are naturally transcended as the jīvātma attains the supreme Self.

It is disconcerting to note the complete and utter dumbing-down of bhakti. Bhakti is not a catch-all phrase for ‘spiritual’ and a basic free-for-all in which one can do whatever one wants without any basic knowledge or adherence to rituals and the procedures laid down by the Ācārya-s. Bhakti is distorted by non-practitioners as a bizarre amalgamation of indistinct terms like devotion, love, and the vagaries of the individual.

There are erroneous assertions that parallels exist between bhakti yoga and ‘devotion’ that is practiced in Abrahamic religions. However, there is no real similarity here because bhakti does not mean devotion and the Śrī Vaiṣṇava ideas of prapatti and śaraṇāgati are non-existent in Abrahamic systems. Furthermore, bhakti is a sādhanā in which one acquires ātmānubhāva, and has stages that takes the bhakta toward the union with Paramātma. Bhakti is not an exchange system wherein one gets salvation in return. The reward of bhakti is bhakti itself – being immersed and losing oneself in the Paramātma, which might result in mokṣa. Mokṣa does not mean salvation. And bhakti does not require dogmatic doctrinal belief in order to gain mokṣa. Bhakti yoga intrinsically believes in an all-pervading Brahman present in every single living and non-living entity, a direct contradiction of the dogmas of the Abrahamic systems.

The Appropriation and revisionism of Āṇḍāḷ

The girls and women who love Āṇḍāḷ, venerate her, honor Āṇḍāḷ as she was in her own words, and have been engaged in their enduring practices now find themselves in a bizarre scenario wherein they are in the crosshairs of Indologists, history revisionists, and feminists. Even the benign and inspiring Āṇḍāḷ is now a target. It is quite impossible to understand Āṇḍāḷ without having performed the sacred vratam she initiated. Conducting pūja-s and observing vratam-s in Hinduism are a form of embodied knowing by which one gains a comprehensive understanding that transcends the emotional and intellectual levels. And performing the vratam every year brings new knowledge and insights of Āṇḍāḷ to the practitioner; it is indeed a life-long journey and sādhanā. However, feminists and postmodernists seek to impose their narrow lens and essentially want to erase Āṇḍāḷ as she was and, in her place, create a new entity who docilely reflects their ideology and agenda. This is not mere speculation, feminists admit that their wish is to remove Āṇḍāḷ from the Dharmika worldview and reinterpret and ‘re-imagine’ Āṇḍāḷ and her works in solely their own worldview. When one reads feminist’s interpretations of Āṇḍāḷ, one cannot help but notice that there is much anger and violence in their language. Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s have kept alive Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s and her legacy for over 1200 years, but feminists, who have only ‘discovered’ Āṇḍāḷ in the last decade or so, truculently accuse Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s of appropriating Āṇḍāḷ. The feminist attack on Āṇḍāḷ and Śrī Vaiṣṇava-s cannot just be laughed away or ignored as this echo chamber has not subsided. Some feminists have gone so far as to advocate changing the types of pūja-s done to Āṇḍāḷ and limiting Hindu devotees’ right to honor Āṇḍāḷ and her works as they have been for centuries.

The re-writing of Āṇḍāḷ’s story by feminists entails re-interpretations, speculative assertions, and also outright blatant falsehoods about Āṇḍāḷ, her life history, and the pūja-s conducted to honor her. For instance, Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s often refer to her detachment from her physical body she obtained in this birth and that her only goal in this life was to attain Śrī Kṛṣṇa. These beautiful pāsuram-s are deliberately distorted by feminists who falsely claim that Āṇḍāḷ was preoccupied with her own body and that her object was physical and material. Materializing the compositions of Āṇḍāḷ is an attempt to muddle and eventually completely distort the motivations of this great girl-Āḻvār. Āṇḍāḷ has stated her motivations herself in her compositions, however feminists seek to dis-empower Āṇḍāḷ and put her life’s work firmly in the realm of materialism. In effect, they seek to reduce Āṇḍāḷ to a mere instrument and seek to make her into a weapon against the very devotees who revere her. Āṇḍāḷ sought mukti of this physical world and of the bondages of the body, yet the postmodernist and feminist seek to imprison her in their mundane worldly lens. It is noteworthy that in the revisionism of Āṇḍāḷ, feminists have even sought the help of western male revisionist historians who are outsiders to the tradition and who do not even know Tamiḻ; this crosses the borders of irony into the realm of outright satire. The question arises: How can a male westerner, or for that matter a female westerner, with no knowledge of the language and a non-practitioner, understand the experiences of an Indian girl? How can a male or female westerner understand Indian girlhood, its experiences, joys, challenges, living its customs, traditions, and way of life? Śrī Vaiṣṇava women and girls are the main protectors of Āṇḍāḷ, through more than a millennium, these women have preserved, revered, and loved this little girl who shared her divine knowledge, but now feminists seek to bypass and relegate these women bhakta-s.

One of the most trenchant criticisms of Feminism even within academia is that it represents, for more than five decades since Feminism’s genesis as a movement in the 1960s, only the viewpoint of the white North American and European woman, leaving out the viewpoints of the rest of world’s women, especially indigenous women. Thus, it seems that feminists now are scrambling to make up for that critique by appropriating and, in many cases, fabricating accounts of Indian female historical figures.

Feminists claim to fight the hegemony of traditionally male-dominated societies and be the champions of women. Ironically however, there is a hegemony within feminism itself; non-western feminists themselves have objected to what they call ‘imperial feminism’ wherein so-called third world cultures are asymmetrically demonized by western feminists. Furthermore, non-western feminists in academia have pointed out that western feminists stereotype native cultures as more oppressive than western culture. Thus, it seems that it is Feminism which requires reform from its own oppressive one-sided theories and pigeonholes which stereotypically portray and trivialize women of other cultures. The demonization of native cultures by western feminists and their followers in India has become the norm and unfortunately, this hegemony of western feminism is espoused by most Indian feminists. Nowhere is this more evident in the speculative and misleading discourses of Hindu religious figures who are revered and whose memory and customs are kept alive by Hindu women themselves. In seeking to force-fit Āṇḍāḷ into the imperial feminist framework, Indian feminists do what they claim to fight against – they belittle and diminish the voice of native Hindu women and their experiences.

Āṇḍāḷ is a powerful unifying symbol for Hindus; she is an embodiment of Indian girlhood. Āṇḍāḷ is a powerful presence in the Indian psyche, so much so that feminists understand that the appropriation of Āṇḍāḷ into their worldview will strengthen their agenda. It warrants notice that many of these appropriators do not know Tamiḻ; and cannot understand the more complex older poetic Tamiḻ that these pāsuram-s are in.

Though some have claimed that there are parallels between Āṇḍāḷ’s sacred songs and those of some Abrahamic poets, this is actually not the case because Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s are firmly rooted in the Veda-s which reflect that Brahman and the jīva-s are without beginning or end, are unchangeable, are present everywhere, and the jīva-s can be in union with Brahman; these concepts are not available in the Abrahamic systems. These fundamental differences are glossed over by revisionists who seek to assimilate Āṇḍāḷ’s works into the Abrahamic one.

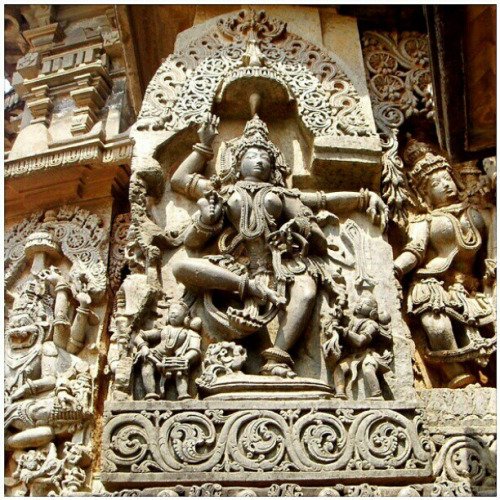

Bharatanatyam and Āṇḍāḷ

Āṇḍāḷ’s pāsuram-s are frequently embodied through Carnatic music and Indian classical dances such as Bharatanāṭyaṃ. This is due to the fact that Bharatanāṭyaṃ itself is an embodiment of Hindu metaphysics. The embodiment of Āṇḍāḷ and her works should be celebrated and nurtured within the Bharatanāṭyaṃ community. However, some feminist elitist dancers lament that Āṇḍāḷ is now being danced by everyone, thus making her pāsuram-s more widely known to the general Indian population, especially in southern India. This is rather strange, after all if one loves and admires something, one wants to share it with the world, not keep it in an inaccessible rarified circle. Just as Āṇḍāḷ wanted to share that glories and beauty of Śrī Raṅganāta with everyone, one who truly admires Āṇḍāḷ would want to share her with the world and not imprison her within the confines of a narrow point of view of feminism or postmodernism. Dancing the pāsuram-s of Āṇḍāḷ is a form of embodied knowing; the act of dancing her pāsuram-s with śraddhā is itself a pūja, a manifestation of bhakti. One can experience some of what Āṇḍāḷ herself speaks of through the dancing of her sacred works and can transcend and elevate one’s limited ego-centric state to something greater.

Conclusion

Āṇḍāḷ, a child with a purest heart is the epitome of pure sāttvika bhakti; her contributions are due to the unique characteristics she possesses. She represents Indian girlhood and speaks to that experience like few others can. Āṇḍāḷ, a young girl of 8 or 9 years whose manas was pure and sāttvik, was determined to attain mukti and finally did so at the feet of Śrī Raṅganātar in Śrī Raṅgam. Any interpretations of her pāsuram-s that are contrary to the sāttvika meaning are mere projections of the adults who want to impose their own laukika view onto this young girl’s extraordinary sacred works. As stated, reading about Āṇḍāḷ brings no understanding of her works and this post is only a cursory glimpse of Āṇḍāḷ. The Tiruppāvai, Nāciār Tirumoḻi, and Āṇḍāḷ can only be understood only through śraddhā, bhakti, and tapas guided by a qualified Ācārya. Āṇḍāḷ’s deep compassion for others and wish to share her knowledge are qualities that endears her to generations of Hindus for more than a millennium. Her works stand apart and hold a special place in sacred literature. Understanding and indeed experiencing Āṇḍāḷ’s sacred pāsuram-s requires śraddhā and a special dṛiṣti, just as Arjuna was granted a divine vision to see the Viṣvarūpa, and requires steady and unceasingly study and sādhanā. Anyone, literally anybody, could write about ‘coming of age’ as it is a common laukika experience that happens to everyone, this is not exceptional. Feminists and others even within the Hindu population erroneously characterize Āṇḍāḷ, her works, and seek to erase her individuality and exceptionalism by falsely mapping her songs to a ‘coming of age’. However, Āṇḍāḷ transcends this mundane world, she does not want to waste this birth, she seeks a divine union of jīvātma and Paramātma, that experience that supersedes all worldly experiences and is rare, unique, and requires a special state of consciousness. This is why Āṇḍāḷ has endured for over 1200 years and will for millennia to come.

Copyright: 2018 Prakruti Prativadi. All rights reserved.

About the Author:

Prakruti Prativadi, an aerospace engineer, is an award-winning author, Bharatanatyam dancer, and researcher. She is the author of ‘Rasas in Bharatanāṭyaṃ’ http://hyperurl.co/nbg0nq which is based on her research of the Nāṭyaśāstra and other treatises.

Bibliography:

- Chari, Srinivasa. Philosophy and Theistic Mysticism of the Alvars. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. 1994.

- Swami Harshananda. Śrī Vaiṣṇavaism Through the Ages. Bangalore: Sri Ramakrishna Math. 2000.

- Varadachari, K.C. Aspects of Bhakti. Mysore: University of Mysore. 1956.

- Swami Harshananda. The Six Systems of Hindu Philosophy. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math. 2009.

- Upanyāsam-s of H.H. Sri Sri Sri Tridandi Sriman Narayana Chinna Jeeyar Swamiji, 2013 -2016.

- Consultation with H.H. Sri Sri Sri Tridandi Sriman Narayana Chinna Jeeyar Swamiji July-August, 2018.

- Rangachari, K. Śrī Vaiṣṇava Brahmans. Delhi: Gian Publishing House. 1986.

- Kaplan, Caren et. al. (Editors). Between Woman and Nation, Nationalisms, Transnational Feminisms, and the State. London and Durham: Duke University Press

- Feminism and Postmodernism, an Uneasy Alliance. 1999. Retrieved July 23, 2018. https://www.marxists.org/subject/women/authors/benhabib-seyla/uneasy-alliance.htm.