Biography

Vishnuchittar was born to Mukunda Bhattar and Padumavalli in Srivilliputtur (less than 100 Km from Madurai) in the Pandya Kingdom. A date range given for his birth is the 8th-9th century CE. The boy developed a sense of devotion and service toward Mahavishnu from a very young age, and he thought of the best way he could serve his deity every day. His natural affinity for the Krishna avatar reminded him of a story of Sri Krishna who sought out Kamsa’s garland maker in Mathura and wore his garlands with joy. Vishnuchittar thereafter created a beautiful flower garden in Srivilliputtur, and would pick a variety of flowers from there to prepare garlands and offer it to Vatapatrasayee, the deity of the temple there. Vishnuchittar continued this practice for long and it is clear from the amazing incidents in his life that Bhagavan bestowed his grace upon this ardent devotee.

A main reference for this introduction to the life and work of Periyalvar is the book by Thiru M.P. Srinivasan [1].

During this time, Sree Vallabha Devan was the Pandya king who ruled from the capital city of Madurai. He was a great and dharmic ruler like so many Tamizh kings and leaders who built Tamil Nadu, the land of the Vedas. While doing a round of the city one night, the king chanced upon a person sleeping alone outside and woke him up. After learning that he was a Brahman who’d returned after bathing in the sacred waters of Mother Ganga, the king requested him to share a dharmic truth with him. The Brahman’s reply was a simple yet amazing Shloka that said:

“search what you want during the rainy season in the previous eight months, what is needed in the night during day-time, what is required in old age during youthful days, and what is essential for the other life, search in the life now.” [1].

The king was lost in thought especially about the direction given in the last part of a shloka that seamlessly blends the earthly cycles and spiritual realm to make that transcendental point so natural. The King’s adviser suggested he invite the dharmic scholars in his kingdom to find a convincing answer to the nature of ultimate reality; regarding paratvam, which could also answer the King’s question- ‘what effort do we put it today, in this world, to attain transcendental bliss’. The King agreed, and offered a purse of gold to any scholar in the land who could debate this issue and convincingly answer this question. Vishnuchittar was directed by the Srivilliputtur deity, Vatapatrasayee, to proceed to Madurai. Vishnuchittar was able to debate and explain to the august gathering present that indeed, Vishnu was the ultimate reality, ‘the indisputable truth that cannot be surpassed by any reality’; surrendering to the feet of Vishnu, the one who grants the Purusharthas would bring Moksha. He was able to substantiate his response on paratvam, and the story goes that the golden purse tied atop the pole bent down toward Vishnuchittar.

The king was overjoyed by the words of Vishnuchittar that eloquently reflected the teachings of Vedanta and answered the question that had confounded him, and hailed him as ’Bhattarpiraan’. As the seer was being taken in an open procession around the city on an elephant, he experienced a divine vision of Bhagavan Vishnu and Mahalakshmi atop Garuda. The devotee of Vishnu was overcome with love and affection for his deity and sang the twelve great verses of ‘Pallandu’, wishing for the welfare and well-being of the infinite divine for many, many years. After this amazing event, he became known as Periyalvar.

Periyalvar returned to Srivilliputtur, dedicated the gold purse to the temple, and continued his service of preparing flower garlands for his deity. He immersed himself within the Krishna avataram and composed his profound Thirumozhi. Baby Andal (Godai Devi) was found near the Tulasi plant in his garden, and Periyalvar brought her up as his daughter. Andal as an ardent devotee of Vishnu, continued the divine service of Periyalvar. She learned from her father’s teachings of the Vedas and Vedanta and soon became an accomplished scholar of dharma. She composed great works, and is revered as one of the twelve alvars. You can read more about Andal in this sublime essay.

It is said that Periyalvar spent his last mortal years in Thirumaliruncholai and at age 85 reached the lotus feet of his deity he had served from birth. This is a brief biography of the peerless Periyalvar. Let us remember the twelve alvars who dedicated their lives to dharma and brought the genuine message of love and peace to the common people through their shraddha and sadhana.

The Twelve Alvars

Poikai Alvar

Puttatalvar

Peyalvar

Thirumalicai Alvar

Nammalvar

Maturakavi Alvar

Kulasekaralvar

Periyalvar

Andal

Tontaratippotialvar

Thiruppanalvar

Thirumankai Alvar

The divine songs of the twelve Alvars form the Nalayira Divya Prabandam. The songs of the Alvars and Nayanmars sung in the native language of Tamizh cut across all classes of the society to touch all people of Tamilnadu. Eventually the Bhakti movement of Hinduism spread all over India and profoundly influenced Indic thought. The Alvars and Nayanmars are a major reason for the unbroken dharmika beliefs of Tamizhs and the prosperity of தமிழ் மொழி itself, which continues to this day. It is simply not possible to fully understand Tamilnadu’s dynamics until one comprehends the depth of its diverse dharma traditions.

A brief review of two important works of Periyalvar is presented noting that this can only be a layperson understanding of the profound ideas they contain. The references and recommended reading at the end of the post may guide readers deeper into these sacred works.

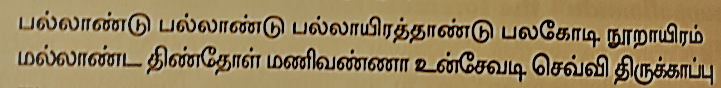

Thirupallandu

ThiruPallandu comprise the opening verses of the sacred Divya Prabandam and has 12 pasurams, each of which end with the words ‘Pallandu Pallandu’ (many, many years). In Tamizh, the prefix ‘Thiru’ signifies the qualities of divinity, sacredness, and respect. The first Pasuram has two lines and the remaining have four lines each.

Embedded within these verses are the deepest truths of Vendanta. A remarkable aspect of these verses is that the devotee’s plea to Mahavishnu is not for himself, but for the welfare of the supreme deity Vishnu. And since Narayana is the One, ultimate reality as Periyalvar explained with Pramanas in the Pandyan capital city, as a layman reader we can understand this plea as one that is automatically for the welfare of everything within and without the cosmos.

The linked video provides brief English translations for each of the 12 verses. A simple translation of the first verse is given below.

“For many years, many years, many thousands of years, many crores of hundred thousands more, The Gem-hued One with mighty shoulders that defeated wrestlers, may your blissful feet (entire form) be well protected and safe.”

Scholars say that just like the Pranavam/Omkaram is chanted before and after the Vedas are recited, so too is the Pallandu, whose depth and meaning is like the Omkaram, chanted before the Divya Prabandam. Vishnuchittar, ardent devotee of Sri Vishnu since childhood, and then a celebrated Vedic scholar after his discourse in the Pandya King’s court, became revered as Periyalvar after reciting the Pallandu. It can be asked how and why this pride of place is given to Vishnuchittar, who was not the first Alvar. Dharma scholars have responded and shed light on a truly remarkable quality of Periyalvar:

When mere mortals and Bhaktas appear before their deity, the request is usually for the all-powerful Bhagavan to protect them and guide them along the path of dharma. But Vishnuchittar asked not for his own protection or guidance, but instead, asked for the welfare of the all-powerful. He is concerned about the well-being of his lord and sings the Pallandu. The thought does not cross his mind, even for an instant, about his ‘status’ and ‘propriety’ and ‘rationality’ behind his request to protect the One who is the supreme protector! Scholar Pillailokaachaariyyar [1] explains this apparent paradox, noting that in the Jnana stage, the protector-protege state remains, and is transcended in the Prema stage where this relationship is reversed by the overflowing love and immeasurable affection of the devotee for the lord. Periyalvar is doing his Mangalaasaasanam to the lord, just as in the Ramayana, the noble Jatayu blesses the divine and all-powerful Sri Rama. The Srivaishnava tradition recognizes Jatayu as Periya Udaiyaar and likewise, Vishnuchittar became Periyalvar and the wise elders accept the Thirupallandu completely.

Scholars note that this Thirupallandu tradition can also be seen in the pasurams of Thiruppavai composed by Periyalvar’s daughter, the divine Andal. They also state that within the twelve pasurams of the Pallandu [1], the “essence of the Vedanta has been concisely rendered and the meanings of the Thirumantiram and Arthapanchakam are also provided succinctly.” There exists a long tradition of the musical rendering of the Pallandu, and as mentioned in the Thiruppavai, the singers were known as ‘Pallantisaippar’ [1]. Bhakta-scholars who experienced the depth and beauty of the Thirupallandu wonder if there is any art comparable to this work and if there is anyone comparable to Periyalvar?

Periyalvar Thirumozhi

Periyalvar’s work has a total of 461 pasurams (473, when we include the Thirupallandu) celebrating the young Sri Krishna starting with his birth and continuing through his divine childhood pranks and events of his early youth. There are 43 Patikams each with 10 or 11 pasurams, with each Patikam considered a Thirumozhi. There is a total of 5 decads (sets of 10 Thirumozhi). In these verses, Periyalvar’s affection for little Krishna, avatar of Mahavishnu, knows no bounds and such is his goodness, such is the integrity of Periyalvar’s devotion that he transcends powerful worldly identities including ‘Jati’ and ‘gender’ to speak of his blissful experiences of the childhood of Krishna as his mother Yashodha, and as the gopikas who adore Krishna. When we listen to the verses, we do not hear Periyalvar the towering scholar and accomplished poet; we simply behold mother Yashodha in front of us bathing little Krishna, singing to Kannan, pleading with him, in awe of her boy, admonishing the divine child for his mischief. It is difficult to find a parallel to this, as another great devotee of Sri Krishna, the Bhakti poet-saint Surdas would later sing: “jo sukh Sur Amar-Muni duralabh, so nandabhamini paavai” – This joy that Yashodha experienced is so special and rare, it cannot be attained even by the Devatas and Munis.

A refocus on these contributions of Periyalvar and Andal would greatly benefit a world that is increasingly divided by gender and class wars and losing itself in a maze of identity-driven dualities.

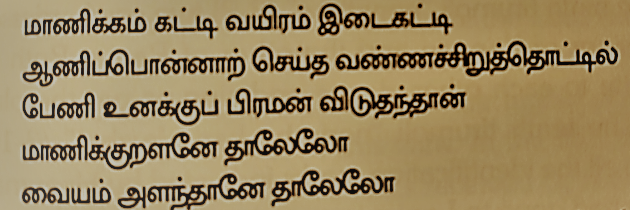

The above ‘Manikkam Katti’ verse is part of a cradle song (தாலாட்டு பாடல்) sung by mother Yashodha as she puts Kannan to sleep in an ornate gem-lined golden cradle. She sings a lullaby to the divine baby ensconced within this small cradle while recalling his Vamana avatar whose strides measure the cosmos! [6].

The verses are full of genuine ‘Krishna-consciousness’ and those fortunate enough to listen to the Thirumozhi without distraction will surely experience bliss too. Such verses could only have emerged from the deepest realized experiences of Periyalvar, and like we saw with Kavichakravarthi Kamban and his Ramavataram before, the literary artistry does not come across as a separate material addition, but could only have poured out of Bhakti and Consciousness.

Two examples from the Thirumozhi are given below to bring out some interesting literary aspects of its poetry.

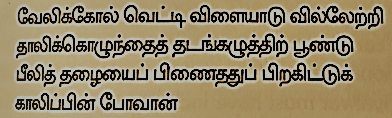

This above verse is focused on Krishna the cowherd who is grazing the cattle and wearing a traditional pendant made of peacock feathers. It is but one of the many verses that is at ease with the folk language, rural themes and traditions, which is very different from the western ‘ivory tower’ erudition that is intended for an academic audience. The verses often include common dialect, and in other places introduces Sanskrit words that are understood and used by Tamizhs. Scholars found several Tamizh words that have no direct English equivalent and have to be retained as is the English translation as Tamizh non-translatables. The commentators note the clear influence of folk literature that makes this work accessible to everyone.

![]()

The part-verse shown above is an example of the use of simile by Periyalvar. He transforms an everyday, common creature like a lizard into poetic delight. He compares the effortless compactness and firmness with which Kannan wears the sword on his waist to the grip of a lizard on the wall without any gap. ‘To be so is the lizard’s nature’ [1].

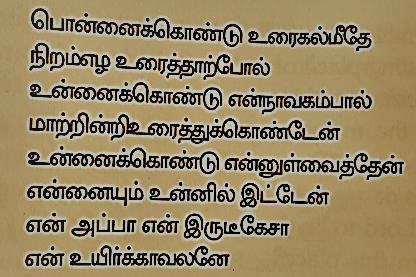

Scholars note that Periyalvar’s work is of the highest caliber in skill, imagination, emotion, and poetic expression. Beyond aesthetics, scholars have also explained how the verses reflect Vendantic concepts and Srivaishnava philosophy. They note that this ending pasuram below brings out a profound concept of Vishishtadvaita, where Periyalvar ultimately places himself in the lord who also resides within him.

What is presented here is a mere glimpse of the contributions of Periyalvar. Let us listen to the Thirupallandu and Thirumozhi and recall Periyalvar whose enlightened thoughts and steadfast Bhakti continue to guide generations of Tamizhs and dharmikas all over the world.

The book by Thiru M.P.Srinivasan can be purchased here.

References and Further Reading

- Makers of Indian Literature Series. Periyalvar. M.P. Srinivasan. English translation by Padma Srinivasan. Sahitya Akademi. 2014.

- Vedics.org: Thirupallandu.

- https://4000divyaprabandham.wordpress.com/category/2-periyalvar/periyalvar-thirumozhi/

- https://alvarsandacharyas.blogspot.com/2007/02/peria-azawar.html

- http://divyaprabandham.koyil.org/index.php/2015/11/thiruppallandu-12-pallandu-enru

- Periyazhvar Thirumozhi: Sublime Hymns of Mystic Consciousness. Vankeepuram Rajagopalan. 2008.

Acknowledgment

TCP thanks dharma scholar Smt. Prakruti Prativadi for her critical feedback. Any error in this article belongs solely to its author.